Moms book (PDF)

File information

This PDF 1.4 document has been generated by Adobe InDesign CS4 (6.0) / Adobe PDF Library 9.0, and has been sent on pdf-archive.com on 18/02/2014 at 18:17, from IP address 198.252.x.x.

The current document download page has been viewed 754 times.

File size: 813.79 KB (41 pages).

Privacy: public file

File preview

סיפור חיים

My

Life

צביה (צילה) רודין

by Cvia Tsila Rodin

translated by Moses Rodin

1

My Life

by

Tsila Cvia Rodin

Thanks to Noy Spiegelman for the beautiful artwork that graces this cover

and that of the Hebrew document

2

The Enemy

I was born on July 13, 1936, the poster child of an enlightened future. Most countries in

Europe had made strides towards civil rights for Jews. The sons of Jacob finally got the freedom

to live as any other citizen.

Families Neuermann and Karabelnicov announced my appearance in this world with

celebrations and bursting pride. My parent’s families were hoping for a bright future. Close

relatives pleaded that I wear the names of their loved ones, so I would wear the name Tsila Cvia

Tiabale Jonah - light to Israel … and Gentiles.

Five years passed, and in June 1941, everything suddenly turned upside down. The rights of

freedom slipped through our fingers like sand and equality melted away like snow in hell. Friends

and neighbors turned their backs and no one came to our aid. The world, an asylum surrounding

us, connived and organized a hunt, a hunt for me, Tsila Cvia Tiabale Jonah, the 5-year-old enemy

of nations.

Protagonists of the Tale

Mother - Batya, the daughter of Lev and Etta Karabelnikov.

Father - Chaim Reuven, son of Yehuda Halevi Neuermann and his wife Tsila.

Those who secreted and saved me Zosia Josephin Tashnioskina

Nun Poishieti Apalobiya Poishieti

Iz’ik the Jewish fellow that guarded the barbed wire around the Kovno ghetto for the

Germans.

First memories

I remember an arrow fired from the country toward the sky.

I remember Berg – the mountain of death – grim and gloomy with a murky black cloud as

its crown. Meandering path led to the killing fields. Sadness stained the air and the sun was

ashamed to shine here. I wore a stifling, black scarf as we passed here. I did not know where we

were going.

I remember a rickety, thrown-together hut at the foot of the high mountain that was the stage

of the unfolding tragedy. The hut is our hotel - mother, father and Tsila. We lived in the shadow

of death, here in our valley of tears.

3

My memory goes no further back, but my mother told me that on the Fifth of August, 1941,

we were expelled from Kovno, from our spacious and comfortable home. The neighbor next

door, Mom’s friend, had entered early in the morning and told my mother that since the Germans

decided to deport the Jewish community in Kovno, she felt, that as a friend, she should get my

parents dining room furniture which my father had purchased new two weeks earlier. This was

our good neighbor, my mother’s friend. With German efficiency, we were whisked to the ghetto

Slebotka, the poorest part of town, dark, grimy and scary.

Ghetto

When I started writing the story, the words came flooding forth. Little effort was needed as

even long-forgotten pieces jig-sawed together and the pages seemed to write themselves. Within

three months the molds were cast. Quickly, I poured in the iron words that were the fortune of

my life.

After I finished, I set it aside. I felt completed, but after a while, when I started to read the

book, I found the story lacking details about life in the Kovno ghetto.

It seemed to me that this place, “ghetto” was so scary and disgusting. My subconscious

refused to break its seal of pain and disgust.

I will have no choice but to retell a few stories my Mother and Father told me - our first

exit from the ghetto and return to that hole, the story of the brave partisan action and murder of

children.

Train Station

We lived for two years in the ghetto Slebotka, a small town near Kovno - Prison for Jews.

A thick air of miserable grey morose and the smell of desperation enveloped the buildings and

alleys, and this was our whole world. Close quarters held men, women and children, yet it was

the children that least understood the nightmare vision. The children’s eyes were watching all

the happenings in the ghetto, their world. They saw Jews, persecuted, hurt and confused and ask,

“What happened?”

Then, in the confusion of the blink of an eye, I stood at a train station at dusk with my mother

and Zosia. For the past few days Zosia hid us in the broom closet of her home. Her husband

was unaware that two Jews stood stiff in this coffin of a room. After he left for the office, Zosia

4

would let us out briefly, for a few minutes we could move. This deception, however, threatened

all involved and we needed to move elsewhere. The train station led elsewhere. It was a huge

building swallowing trains and belching in and out countless people scurrying from place to place

like rats in a maze. I was shocked that we were here, but the shock blended fear with confusion.

Even Lithuanians feared German soldiers. Eyes were lowered and prayers to any grasped deity

were muttered on pursed lips.

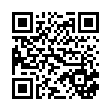

I wore a blue coat with fur collar gray my hair blonde and dark brown eyes.

Ghetto girl eyes. My mother, however, was like a totally gentile Lithuanian. She had reddish

blonde hair, her eyes were green, and somehow, she

summoned a proud march, full of firm confidence

and good appearance. All this cloaked the fact that

there was a terrible fear in her heart that secreting

me away to safety was as if one needed to hold a

shadow. But she was determined that no obstacle

or calamity could stop her. This thought has been

etched in all her essence - heart, soul and body.

Days earlier, Mother had said,”Chaim, I’m going to

take the Tsila (for the second time) from the ghetto

and do not try to convince me otherwise. Please, I

beg you, and all the family not to talk about it.” To

me, no one in the family mentioned our escape from

the ghetto until the evening we left.

I just found myself outside the ghetto in Kovno

train station on the way to the village. Zosia went to

the ticket window to buy tickets. Mom and I were

just watching what was happening. Mom held my

hand, seconds ticked and her grip tightened. She

pressed my hand so hard. It hurt so much. I pulled

away but still clutched and pulled at her sleeve. She

bent down and I whispered in her ear, “Mommy,

don’t worry, when I get to the village, I will write you a letter. If I draw a beautiful house, you

can come to me.” Mom kissed me and said, “Great idea Tzilinka.” Tears streamed down her

eyes.

הגטו

Zosia returned with tickets. Zosia and mother whispered quietly.

.זרמוmoved

הנובלה שלי

פרקיI רבה

בקלותon

.מעטי

המילים נבעו

,סיפורי

לכתוב אתapproached

כשהתחלתי

Mother let go of me and

away.

sat down

a bench

nearby.

A stranger

גמרתי

שלושה

אוand

מאמץunbutton

מעצמו בליher

נכתבcoat

שהכל

הרגשתי

me and wanted to sit on

the.התקשה

bench. עטי

Sheחודשים

handed

me תוך

her.עמל

purse

before

she

.

חיי

הגדת

את

settled down. You must remember that I spoke no Lithuanian, I saw Mom’s eyes filled with

despair and Zosia was frozen

in the

knowledge

thatאחרי

I only

word,

לקרוא את

כשהתחלתי

,זמן מה

אבלspoke

.יצירתיYiddish.

ביקרתי אתWithout

נחתי ולאsaying

,שסיימתיa אחרי

I took her purse and held it until the woman opened

theבגטו

coatחייand

sat down.

gave her

the ,purse.

.קובנה

פרטים על

חסריםIשבסיפור

גיליתי

ספרי

Zosia and mother were relieved. Zosia moved me to the next seat and sat in between the woman

ההכרה שלי סירבתי- היה כה מפחיד ומבחיל שבתת," "הגטו,נראה לי עתה שהמקום הזה

and me.

. בשל הכאב האיום שסיפור הגטו גרם לי,לפתוח את הדפים של ספרי

כגון היציאה הראשונה מהגטו,בלית ברירה אצטרך להיזכר בספורים שאמא ואבא ספרו לי

. סיפור הפרטיזנים האמיצים האקציה של הילדים וגם הרצח,והחזרה לגטו

5

The rule was simple: to anyone who gives safe harbor to a Jew, a death sentence

applies to them and their family. I knew it, every Jewish child knew it.

We all relaxed. I was with Zosia and mother, and I felt mother hugging my shoulders. I looked

around, people came and went, trains came and went, and I kept thinking I was seeing Father’s

smiling eyes, his soft face. My loving father was a wise and good man. Yet I knew that he was

alone, praying to God that everything would go well, willing that mother would return in safety

and security to his arms. I was pulled back to reality by a terrible screech and evil hiss as a train

pulled in front of us. Mom whispered to me in Yiddish to go with Zosia to the train. She kissed

me and said, “Zie Gezunt Mine Kinder.” Tears flooded her beautiful face. She squeezed my hand

and said thanks to Zosia. We had to leave. Zosia put small suitcase on my shelf and sat me next

to the window so I could look at Mother. Zosia sat tight by my side. Mother waved until the train

left. I waved back until it disappeared on the horizon. I did not speak or cry. A ghetto girl knew

not to speak or cry. Mother returned to the ghetto before curfew. In the evening, I was tired and

fell asleep. It seems I slept until we reached the village. Zosia woke me very rapidly and we

picked up our packages and quickly went down the stairs of the train station. Zosia walked before

me with a suitcase and package, I clung to her.

There was a wagon with a horse next to the platform. Zosia put the packages on the ground,

lifted me by the arms, put me in a wagon, and covered me with a blanket. The sad expression

on her face indicated that she was worried I might speak so she put her finger to her lips to quiet

me. She put the suitcase and packages on the cart, and dragged a blanket over my head. She sat

beside the coachman, and the horse took off. Zosia and the driver chatted. I listened quietly to

the clomping of the horse’s hooves. I was awake, I thought of my father and mother. I committed

to writing a letter as soon as we got to the farmhouse, painting a beautiful house with flowers and

trees and the sun shining. Mother and Dad needed to know it was good.

Home – Poishieti’s Village

When I opened my eyes, the wagon was in front of a log house built from forest trees. I picked

up the blanket so I could see the new place where I would live without Mom and Dad, with people

who I did not know. But a Kovno ghetto girl did not cry, a Kovno ghetto girl did not require

anything; a Kovno ghetto girl did not speak. As Mom whispered to me in Yiddish before I left

“you must be a good child.”

I was at the home of Fosckiti. There was a huge barn and a vegetable garden, many trees and

a small lake. Before I left the ghetto, Dad told me Poishieti, Zosia’s sister, was a nun. She was

single and had dedicated her life to Christian worship. She and her family would take care of me

and love me. The monastery that belonged to the nuns allowed Poishieti to hold their property.

6

There were other people there; one farmwoman and her husband and a young Gypsy man to help

her to manage and work on the farm.

Zosia knocked on the door and her sister opened the door. They looked at each other and

hugged and kissed immediately. They began to speak Lithuanian. I did not understand a word

but I knew the subject. I tried not to let them see me. I was scared and I wanted my mother and

father. I had tears running down my face.

I was like a small point in all this space, fields, trees and farm. I washed and put on my blue

coat with a gray collar and a thought came to my mind if there is no good after the war, I’ll go to

Israel. In Israel were my grandparents. Mother wrote a note with her parents’ address and sewed

it inside the collar. Mom stressed that I had to keep the blue coat.

Zosia held my hand and a suitcase and entered the hut. There was no floor, just dirt, a rickety

table, thick glass windows that you could barely see through, a wooden barrel stood on the wall

and a bed in the corner. There was another room with a bed and a closet and another closet that

only held a bed. This was to be my cell. Zosia put the suitcase on the bed and said in Lithuanian

that this is my bed. I understood her because she reached for the bed, and then introduced me to

Poishieti, who was a little old lady with kind eyes and a smiling face. “This is Stasia,” she said

and pointed at me. This name was my new name. It took me a short time to recognize that. No

more Tzilinka, Stiebel or Cvia. My name was Stasia. All my documents said Stasia. Poishieti

watching me, I was small and skinny because of the lack of nutrition, my face was round, full of

life and red with excitement. I had lots of blond curls and dark eyes, ghetto sad, but bright. She

took my hand and spoke to me at length and finally hugged me and said “Welcome, Stasia.”

The next morning was nice and warm. We went into the yard and sat on the bench in front

of the house. Suddenly I remembered my parents and my promise. I went back to my room

quickly, opened the suitcase and immediately found the paper and pencil Dad placed within so

I could write them a letter. I drew a nice house, a bit like the hut of Poishieti, flowers, trees and

sun. As I thought about where my parents were, I remembered the ghetto was not sunny. Clouds

swallowed it. The flowers were gray, and the trees were bare. There was no life in it, at least in

the eyes of a child of five. I looked at the picture and I was not satisfied. I drew another picture

and spent all day on it. I then searched for Zosia. I told her “Mama and Papa.” Zosia knew and

understood a little Yiddish but forbade me to talk to her Yiddish.

Years later, I learned that when my mother stole from the ghetto to explore my fate,

Zosia handed her the letter picture. Mom was happy. By the way, Dad kept the

letter until he reached Dachau, but unfortunately once in a moment of danger, hid

the letter in his mouth and swallowed the paper.

After I gave the letter to Zosia, I was satisfied; I laid my head on the pillow and fell asleep.

In the morning, a beam of light woke me up and I knew not where I was. I looked around and

remembered that I was in the house of Poishieti, sister of Zosia. The truth was that I first saw

Zosia just days before, but Dad told me she was a good and generous person. She worked for

Grandpa and had helped Aunt Luba run the house and raised her young family. After I heard what

my Father said, I felt good with her and trusted her.

I got up still wearing the same clothes as when I got there. I saw Zosia and Poishieti in the

7

next room, sitting next to the rickety table, drinking milk, eating fresh bread from the oven and

deep in conversation. When they saw me, they smiled and motioned for me to join. They gave

me bread and milk. The bread was fresh and delicious, I ate the whole slice before I sipped warm

creamy milk. I never drank a drink so good before. I smiled and said “a dank.” After breakfast,

Zosia and I went back to my room. Zosia opened my suitcase and gave me a dark skirt and yellow

sweater. I got dressed and went outside into the yard. We walked toward the barn. It was a huge

wooden building with an unbelievably high ceiling. I could hardly see the end of the building.

The building was packed with bundles of hay and fodder and wheat. At the end of the barn were

the animals - cows, a horse and pigs. Several of the large pigs were very fat and some smaller

pigs had glistening skin. There were also chickens, ducks and geese. There was a tall, thin man

wearing work clothes and holding a pitchfork. A plump woman with blue eyes and gray hair

wearing a floral dress and white apron stood by him. It was probably his wife. Past them was a

young man, very tan with black hair. He looked just like the description I had heard of a Gypsy.

Everyone knew Zosia and asked how she was. Zosia introduced me to the workers of Poishieti.

“This girl is named Stasia and is from Kovno. Unfortunately, her parents were killed in a car

accident. She is five and has not spoken since the accident. Please treat her gently; her condition

may improve over time. She is staying here under the supervision of Poishieti.

By the way this story and the forged papers were created in the ghetto.

The woman nodded and said, “We’ll take care of the poor girl and be good to her.” Zosia

thanked them and left the barn. We walked slowly through the farmyard. Here, in the wilderness,

the sun and the fields were all in gold and blue flowers dotted the landscape. Zosia said in Yiddish,

“It’s very beautiful, it’s very beautiful, Tsilinka. Tomorrow I’ll go back to Kovno. I’ll talk to your

Mom and Dad. You must not speak Yiddish.”

Zosia’s leaving surprised me. I never thought I would stay here alone. I started to cry, but

the sight of the lovely scenery somehow calmed me down and I quit worrying. Peace washed

over me as Zosia and I walked through the golden fields. Occasionally, I would stop to pick wild

flowers and Zosia patted my head. I was happy. We returned to the house. Poishieti stood before

the table covered with food - bread, butter, cheese and sweet milk. Poishieti recited a blessing

before we ate a satisfying meal. Immediately after dinner, I added gold fields and blue flowers to

a drawing I made for my parents. Though I did not have colored pencils, I knew they would see

the colors in their imaginations. I gave the second letter to Zosia.

Night was falling and the room was chilly. Poishieti put wood in the fireplace the whole house

warmed up. I sat on the dirt floor before the fire, watched the flames and drifted off to sleep.

Zosia picked me up, dressed me a nightgown, rested my head on the pillow and whispered to me

in Yiddish that she would return to Kovno the next day and give the letter to my parents. She

added, “Tzilnka, be a good girl and make sure to listen to Poishieti.” She kissed me and I fell

back asleep.

8

Stasia’s New Life

I got up with the sun. I looked around and no one was home. Zosia had left for Kovno and

Poishieti was absent. Dread fell on me and I ran outside without anything on but a nightgown.

In the distance, I saw Poishieti and called to her. She came quickly and we went to my room and

she helped me get dressed. Without saying a word, we sat down and ate breakfast. We ate slowly

and I remembered that it had just been days since I was in the ghetto.

Food was scarce in the ghetto, subsisting of a little bread and a few vegetables. I had

become sick and my vision was blurry. The doctor said I suffered from malnutrition.

Mom did not let the danger assuage her, left the ghetto and traded some jewelry

for butter, sugar, cheese, bread, jam and other delicacies. We ate our fill and we

thanked God for the blessing. Soon, my vision improved. It was one of the few good

memories of those hard times.

I helped clear the table and left the room. The smell of spring was in the air and the trees were

wearing colorful flowers. Plenty of fruit trees flourished here, pears, apples and cherries. My

heart was filled with joy and happiness at the sight of this landscape. I missed my parents but the

serenity and beauty was wonderful. Best of all, I was not in the ghetto!

Several days passed. It was a Sunday and a sumptuous meal covered the table. There was

bread, eggs, butter, sliced cheese and ham slices. I ate the egg and bread and drank milk. I did

not touch the ham.

I remembered in the ghetto, even in the worst of times, my parents did not eat pork.

Mom and Dad argued about it.

Mom said, “We live, we do not eat unclean animals, the Nazis do not win, not in my

house.”

Father answered, ”Batya even rabbis say that saving lives permits the eating of

anything.”

Mom insisted and we ate no pork.

Now Poishieti motioned me to eat a pork slice, I took two pieces and chewed the red meat.

When she turned around, I took the white part of the fat and I ran to my room. I pushed back a

board and hid the fat behind it. I did not imagine what would happen after a few days. Poishieti

smelled an acrid stench in my room. The rotten, stale smell of the pork fat came through the wall

slats. She talked to me at length but I was unable to explain the smell. She finally found the pork,

but never knew why I did it.

The days passed peacefully, the sun warmed the earth; all flowers and fruit trees bloomed. The

food was delicious and there were no Germans. Sometimes I lay on the grass and imagined all

9

Download Moms book

Moms book.pdf (PDF, 813.79 KB)

Download PDF

Share this file on social networks

Link to this page

Permanent link

Use the permanent link to the download page to share your document on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or directly with a contact by e-Mail, Messenger, Whatsapp, Line..

Short link

Use the short link to share your document on Twitter or by text message (SMS)

HTML Code

Copy the following HTML code to share your document on a Website or Blog

QR Code to this page

This file has been shared publicly by a user of PDF Archive.

Document ID: 0000147357.