edo in 1868 (1) (PDF)

File information

This PDF 1.4 document has been generated by Prawn, and has been sent on pdf-archive.com on 17/11/2015 at 21:29, from IP address 129.128.x.x.

The current document download page has been viewed 982 times.

File size: 5.52 MB (30 pages).

Privacy: public file

File preview

Edo in 1868. The View from Below

Author(s): M. William Steele

Source: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Summer, 1990), pp. 127-155

Published by: Sophia University

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2384846

Accessed: 16-11-2015 21:47 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Sophia University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Monumenta Nipponica.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Mon, 16 Nov 2015 21:47:14 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Edo in 1868

The View fromBelow

T

by M. WILLIAM STEELE

durof Edo commoners

NHE presentarticlefocuseson theexperiences

ing 1868. It examines the ways in which they were affectedby the

political,economic,and social changesthataccompaniedthe collapse

of the Tokugawa bakufu and the establishmentof the new imperialregime.

Duringthistimethemen and womenof Edo, caughtbetweentheold and new

regimes,were pulled in conflictingdirections.On the one hand theywere

residentsof Edo, theheadquartersof theTokugawa familyand politicalcenter

of Japan formorethan 250 years.They saw littlegood in the countrybumpkins fromSatsuma and Choshfuwho spoke a rough language and acted in

disregardof conventionand morality.And yettheTokugawa familyhad been

defeated;theold regimewas dead and theywereforcedto liveunderSatsumaChoshtuoccupation.Theyhad no choicebutto becomeresidentsof Tokyo and

bow down beforean unfamiliaremperor.

The Meiji Restorationhas oftenbeen portrayedas a 'soft' revolution:in a

smoothif not rationalmanner,feudalismwas replacedby a centralizednation

state. Recent studies, however,have stressedthe trauma of the transition.'

Whileattentionhas been paid to peasant unrestduringthisperiod,littlework

has been done on the Edo townsmenwhose politicaland economicfortunes

were perhaps most affectedby the collapse of the old regime.Here we are

concernedwiththeirplight,caughtin betweenand yet desperatelytryingto

understandthe old and new.

Edo merchants,artisans,and laborers had long and close ties with the

Tokugawa family,but thepoliticaland economicpoliciesit had pursuedafter

diminishedthe enthusiasmof

the openingof the countryin 1853 increasingly

THE AUTHOR is professorof Japanesehistory

at the InternationalChristianUniversity.He

wishes to thank Dr Mark Elvin, Australian

National University,for his comments on

an earlier draft of the present article. He

also acknowledgesthe fundingreceivedfrom

the Ray-Kay Foundation to carry out the

necessaryresearch.

Japanesedates are givenin year-month-day

order; i=intercalary.

1 Thomas M. Huber, The Revolutionary

Origins of Modern Japan, Stanford U.P.,

1981. See also Tetsuo Najita & Victor

Koschman,ed., Conflictin JapaneseHistory,

PrincetonU.P., 1982.

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Mon, 16 Nov 2015 21:47:14 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

128

MonumentaNipponica, 45:2

theirsupport.Theyrealizedthatthebakufuwas unableto wardofftheforeign

barbarians.2The Tokugawa familyseemedhelplesseitherto protectthecountryfromforeigninvasionor to providethe basis fordomesticlaw and order.

By 1868 Edo commonershad become disenchantedwithTokugawa rule.

On theotherhand theywereambivalent,ifnot opposed, to thenewimperial

systemand the politicaldesignsof the men fromSatsuma and Choshui.They

weredismayedbythenewsof thedefeatof Tokugawa forcesat Toba-Fushimi

duringthe firstweek of the new year, 1868. They feared for theircityas

imperialtroops advanced on and finallyoccupied Edo in the spring.Many

townsmenactivelysupportedthe resistanceactivitiesof the Shogitai#A4z

(a band of youngpro-Tokugawadiehards)and otheranti-imperial

forces;certainlytheylamentedthe defeatof the Sho5gitai

on 1868.5.15. By late summer

theyweretold thattheircitywas to be renamedTokyo, the EasternCapital,

and finallyin the autumn,on 10.11, theywere forcedto bow down to the

boy emperor.A worldhad passed, but fora briefmomentthe social lid was

liftedto allow a unique glimpseinto some of the bottom-layer

attitudesand

propensitiesof the Edo commoners.

Naturallythesourcesavailable forresearchon late Tokugawa social history

are limited.Commonerswerenot concernedto writedown theirpoliticaland

social viewsin anycoherentfashion.A hodgepodgeof documentary

evidence,

however,is available: diaries, petitions,inflammatory

statements,mocking

rhymes,satiricalcartoons,kabukiplays,popular literature,

crudenewspapers

(both Japaneseand Western),broadsheets,handbills,and evengraffiti.

In adKatsu

Kaishfi

the

dition,

Tokugawa retainerwho playeda leadingrole

WV4,

in mediatinga settlementbetweenthe formerbakufu and the new imperial

regime,lefta diarydetailingthe eventsof 1868. As he was particularlysympatheticto the plightof the common people and oftenrecordedhis impressions of social conditionsin Edo, the diaryis especiallyhelpfulin helpingus

understandhow the commonersexperiencedthe Restoration.'

A BoilingCauldron

On 1868.19.2, as the imperialarmywas makingits advance on Edo, Katsu

Kaishfusummedup the situationin Edo as follows:

2 M. William Steele, 'Goemon's New

World View: Commoner Representationsof

the Opening of Japan', in Asian Cultural

Studies, 17 (1989), pp. 69-83.

3 Major sources for bakumatsu social

historyinclude Sakuragi Sho

, Sokumenkan Bakumatsu-shi I

Godo,

& Koike Sho1975; Suzuki Tozo6

taro

6Jvffitc13, ed., Kinsei Shomin Seikatsu

4:

Shiryo: Fujiokaya Nikki

jt o

NP1W H6E, San'ichi, 1987- (10 volumes

planned); Suzuki Tozo & Okada Satoshi 0I M

1

,- Tokyodo, 1985, 3 vols.; and Yoshino

Masayasu -JAf , Kaei Meiji Nenkanroku

m ,tic

W i 8-ii

Gannando, 2 vols., reprint,

1968.

Secondary sources include Minami Kazuo

4i

f- , Ishin Zen'ya no Edo Shomin l-%NihslfR

1 wIP , Kyoikusha, 1980, and Yoshihara

Ken'ichiro lV R NS, Edo no Johoya:

c' -1F

BakumatsuShomin-shino Sokumen i1 CO

cJ

NHK Books, 1978.

tgW g t

f18HIJL,

j4t,ed., Edo JidaiRakushoRuiju i-i X

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Mon, 16 Nov 2015 21:47:14 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STEELE:

Edo in 1868

129

10 g0_

of rice

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

l

1853 '54

l

l

'55

'56

l

'57

l

l

I

,

I

'58

'59

'60

'61

'62

,

'63

,

'64

,

'65

,

'66

l

'67

'68

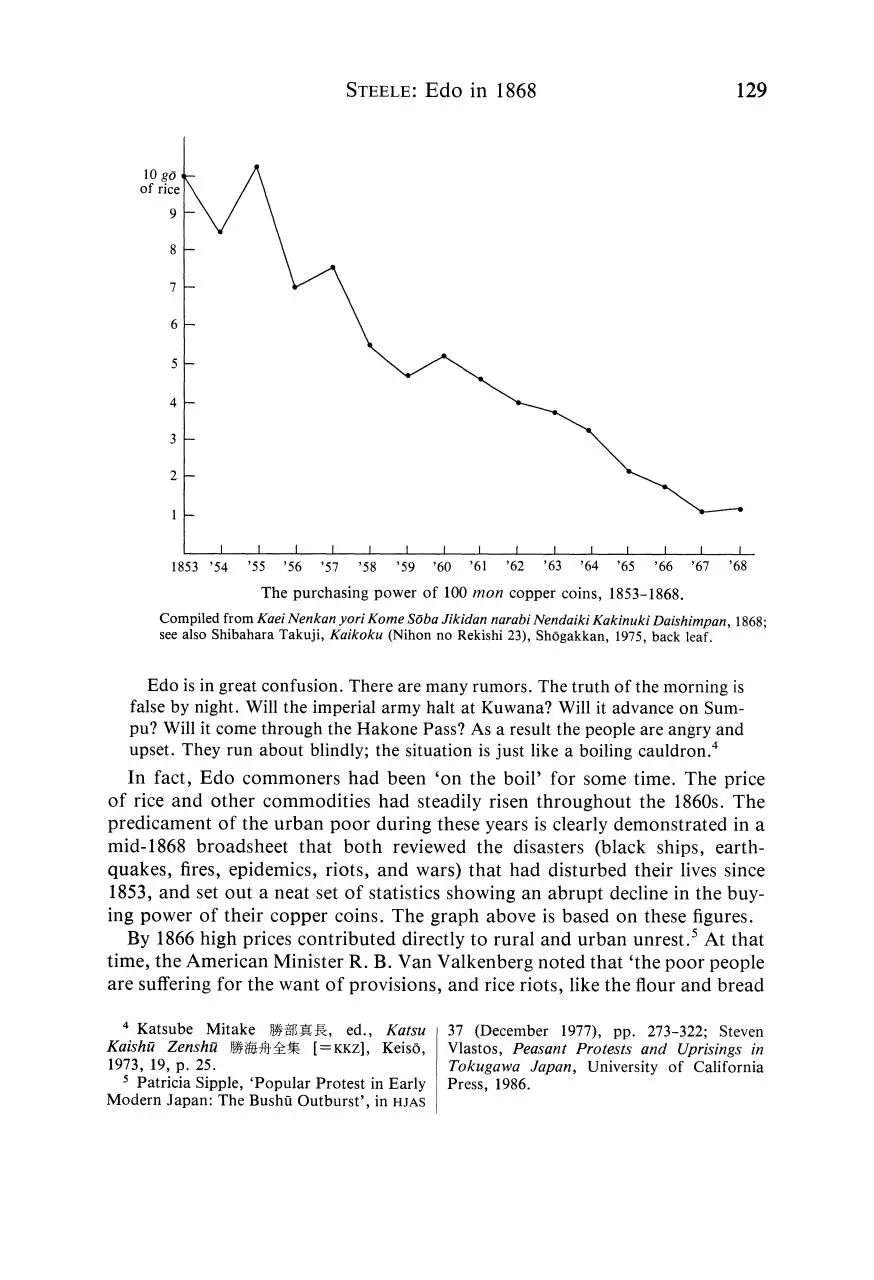

The purchasingpower of 100 mon copper coins, 1853-1868.

CompiledfromKaei NenkanyoriKome Soba JikidannarabiNendaikiKakinukiDaishimpan,1868;

see also Shibahara Takuji, Kaikoku (Nihon no Rekishi23), Shogakkan, 1975, back leaf.

Edo is ingreatconfusion.

Therearemanyrumors.

Thetruth

ofthemorning

is

falsebynight.Willtheimperial

armyhaltat Kuwana?Willitadvanceon Sumpu? Willitcomethrough

theHakonePass? As a resultthepeopleareangryand

upset.Theyrunaboutblindly;thesituation

is justlikea boilingcauldron.4

In fact,Edo commonershad been 'on the boil' for some time. The price

of rice and othercommoditieshad steadilyrisenthroughoutthe 1860s. The

predicamentof the urban poor duringtheseyearsis clearlydemonstrated

in a

mid-1868 broadsheet that both reviewedthe disasters(black ships, earthquakes, fires,epidemics,riots,and wars) thathad disturbedtheirlives since

1853, and set out a neat set of statisticsshowingan abruptdeclinein thebuying power of theircopper coins. The graphabove is based on thesefigures.

By 1866 highpricescontributeddirectlyto ruraland urbanunrest.5At that

time,theAmericanMinisterR. B. Van Valkenbergnotedthat'thepoor people

are suffering

forthewantof provisions,and riceriots,liketheflourand bread

4 Katsube

Mitake

)W

Kaishu Zenshiu O49:t{

1973, 19, p. 25.

A-, ed., Katsu

[=KKZ], Keiso,

5 Patricia Sipple, 'Popular Protestin Early

Modern Japan: The BushfiOutburst',in HJAS

37 (December 1977), pp. 273-322; Steven

Vlastos, Peasant Protests and Uprisingsin

Tokugawa Japan, Universityof California

Press, 1986.

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Mon, 16 Nov 2015 21:47:14 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

130

MonumentaNipponica, 45:2

riotsof morecivilizedcountries,are frequent.Mobs at timeshave paradedthe

streetsbreakinginto ricewarehouses,and committing

othercrimesattendant

upon such emutesof thepeople.'6 In factEdo had suffered

frommajor bouts

of mob violence,beginningin 1866.5. Rice shops,pawn shops,sakeshops,and

of merchantswho profitedfromforeigntradewereraided

the establishments

and wrecked.7

on the Tokugawa

People werequick to place the blame fortheirsufferings

government.

In late 1866a piece of graffiti

was foundpastedon thedoor of the

citycommissioner'soffice:'Owing to high prices,goods are in shortsupply

and able officialsare all sold out.'8 Katsu also ascribedthe social discontent

of 1866 to a failureof bakufu leadership.In his diary he predictedthat if

administrativereformswere not instituted,rural and urban unrestwould

spell the end of Tokugawa rule.9

Edo commonerswerenot only aware of the economicills of theirsociety;

theywerekeenobserversof thepoliticalsceneas well.An unsignedwoodblock

of the political

printissued in 1867.3 is good evidenceof theirunderstanding

problemsof the day. Titled 'TreatingDifficultDiseases', the printportrays

a situation where patients (political leaders) seek cures for ratherstrange

diseases. The daimyo of Satsuma, for example, suffersfromthe 'long-arm

disease'. In thecaptionhe says: 'In thisconditionI seemalwaysto be wanting

thingsthatbelongto others.What am I to do? Please don't letme die.' Other

daimyoare similarlyinflictedby raremaladies: the 'show-only-your-backside

disease', the 'no-backbone disease', the 'no-face disease', the 'mouth-only

disease', and so on. Tokugawa Keiki (or Yoshinobu) S)I11 5', who was

fromdepressionbroughton by the

appointedshogunin 1866.12, is suffering

of

fetters his office.He is made to say, 'If only I could retireand turnover

thesebothersomedutiesto my son.'

While the printis a humorouslook at the problemsof the politicalelite,it

also portraysa profoundcynicismfeltbythecommonerstowardtheirsamurai

masters.The people were concernedabout but also criticalof the failureof

theirleadersto save themfromeconomicand politicalconfusion.As theprint

itselfnotes: 'The famousdoctorwho acceptedthesepatientsalso gave up.'10

Any hope that the new head of the Tokugawa familywould come to the

6

Dispatch from Mr. Van Valkenbergto

Secretaryof State, dated 5 November1866.

Papers Relatingto ForeignAffairs,AccompanyingtheAnnual Message of thePresident

to theSecond Session Thirty-Ninth

Congress,

Government Printing Office, Washington,

1867, 2, pp. 226-27.

7 For the details, see the chapter on the

1866 Edo riotingin Minami Kazuo, BakumatsuEdo Shakai no Kenkyii

aI)t=a

Wt, Yoshikawa, 1978,pp. 266-324. Minami,

Ishin Zen'ya, pp. 147-58, summarizesthis

chapter.

8 Quoted in

Minami,Ishin Zen'ya, p. 157.

9 Zoku Saimu Kijii

Nihon

ShisekiKyokai, 1922, 5, pp. 132-33.

10 MinamiKazuo has analyzedthisprintin

Ishin Zen'ya, p. 190. A copy of the original

printmaybe foundin theShiryohensanjoCollection,Universityof Tokyo.

Othercollectionsof late Tokugawa popular

printsare preservedin the Tokyo Municipal

Library (Tokyo Toritsu Toshokan) and the

National Museum of Japanese History(KokuritsuRekishiMinzoku Hakubutsukan).

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Mon, 16 Nov 2015 21:47:14 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STEELE:

*. ..

.....

...

. &

:

........:

.

..

131

Edo in 1868

-

TokyoUniversity.

Shiryohensanjo,

'TreatingDifficultDiseases.

rescueof theEdo commoners

was confounded

by hispetitionof 1867.14.10

forpermission

to return

politicalauthority

to theemperor(taiseihokan7k*

declared

s) The newscaused havoc in Edo; some Tokugawaretainers

themselves

readyto carryouta coupagainstKeiki.l Thecommoners,

already

suspiciousof hiswell-known

infatuation

withthingsWestern,

concludedthat

Keikifeltno concernfortheirsafety

andwelfare.

A mocking

rhyme

popularin

late1867condemned

Keikias an 'evilking'.12Atthesametimetheresidents

of

Edo werebuffeted

by a rashof murders,

and otheractsof terror.

robberies,

Beginning

in late 1867.10and continuing

wellintospringof 1868,gangsof

hoodlumsroamedthestreets

ofEdo, destroying,

as faras thecommoners

were

anysemblanceof law and order.Whilesomeof thelootingwas

concerned,

donebytheEdo poor,muchof it can be attributed

to Satsumamen,someof

whom,it wassaid,hadbeensentbySaigoTakamorigW4Wihimself.

Satsuma

roniniRX,callingthemselves

the 'SatsumaAdvanceGuardof theImperial

Army'(KangunSempoSasshu-han

'8gSi)Il'l)

wereclearly

responsible

forsetting

firesand instigating

riots.On theone handtheyurgedthepeople

to rebelagainsttheevilTokugawaauthorities,

andon theotherwarnedthem

l Shibusawa Eiichi R

S8;5R;toD

et

HE, in Kyoto

Tokugawa K5do' g>

Keiki-ko Den 4 1IIFXfi~, Toyo Bunko re- DaigakuKyoikuGakubuKiyoegW tPM

print,1968, 3, pp. 256-57.

IVEO, 30 (1984), p. 18. The originalsourceis

12 Quoted in MotoyamaYukihiko*[1A,

Sokumenkan

Bakumatsu-shi,

2, p. 763.

'Bakumatsu ni okeru Minshu no Ishiki to

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Mon, 16 Nov 2015 21:47:14 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

132

MonumentaNipponica, 45:2

to fleein orderto escapeinjuryin theupcoming

civilwar.One oftheirhandbillsdeclared:

In recentyearsevilofficials

of thebakufuhaveignoredcourtauthorities,

made

pactswithWestern

barbarians,

slighted

thecourt,and destroyed

thepropriety

betweenlordand vassal.Therefore

thegreatlordsof thewestern

domainsare

in orderto eradicatetheevilbakufuofficials.

cooperating

theshogun

Although

hasreturned

politicalauthority

to thethroneandis nowsimply

oneofthelords,

in theKantoignorethis.Theysecretly

evilofficials

plothowto graspauthority

onceagain.Therefore

we proposethegreatplanthatall determined

menin the

nationgathertogether

on 11.4 and forma 'heavenlyarmy'[tempeiI4] to

burnEdo Castleand setfiresthroughout

Edo cityand punishtheevilofficials.

Theonlythingthatweareafraidofis thatthepeoplemaysuffer

becauseofthis.

You shouldquicklymoveyourbelongings

and changeyourresidence

to avoid

harm.We do notintendto harmthepeople,onlyto savethem.13

Edo commoners

wereyettoturnto Satsumaforsalvation.Frenzieddancing

to theshoutofEeja naika,eeja naika ('Ain'titgreat!Ain'titgreat!')providedsomeoutletfortheirfrustrations.

The crazehitEdo inthe12thMonth,

justatthetimewhentroopsfromSatsuma,Choshu,Hizen,andTosa seizedthe

imperialpalace gatesin Kyoto,declaredan imperialrestoration

(oseifukko

abolishedtheTokugawabakufu.14

T_AY), and formally

Edo UnderSiege

Newsofthe1867.12.9coupd'etataddedto thegeneralstateofalarmthatexistedin Edo. TroopsfromShonaiand theShinchogumi

ViR6a,a Tokugawa

inan attempt

to restore

policeforcecomposedlargely

ofronin,

wereemployed

law and order,butto no avail. Earlyin themorning

of 12.23theNinomaru

of PrincessSeikan-int

palacewentup in flames.As it was theresidence

PrincessKazu Tl,widowof theshogunTokugawalemochi#,)II*j

(formerly

and auntof theMeiji emperor)and Tensho-ini

(widowof Tokugawa

lesada #)IIt and adopteddaughter

of ShimazuNariakira

) rumors

ascribedtheconflagration

threatened

to

to Satsumaronin

whohadpreviously

forcesinEdo

liberate

theseladiesfromEdo. Two dayslaterthepeace-keeping

tooktheirrevenge:theSatsumaresidence

was burntto theground.

Commoners

mayhaverejoicedwhentheSatsuma'hoodlums'weredriven

out of Edo, but theirhappinesswas short-lived.

News of the defeatof

Tokugawaarmiesat Toba-FushimireachedEdo on 1868.1.12.Tokugawa

Keikihad beendeclaredan 'enemyofthecourt'and an armyof chastisement

was soon directedagainstEdo.

Keiki'sflight

backto Edo becamethesubjectofpopularridicule.Leavingin

taken

thedeadofnightand losingtheirwayat sea, Keiki'sentourage

wasfirst

13

Teibo Zatsushiuroku

TYMM,

Nihon Richard Minear, 'In Pursuit of the Millen-

ShisekiKyokai, 1923, 1, p. 104.

14 For the Ee ja nai ka movement, see

nium', in Najita & Koschman,pp. 177-94.

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Mon, 16 Nov 2015 21:47:14 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STEELE:

-4

Edo in 1868

133

~'R

WE'Se-~~~~~~~~~~

)

.:J~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

..... ...

.2~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~>~~~

.~~~~~~:;.....~~~~~~~~~~.

....

'The Toba Battleof Farts.'

Author's collection

aboard an Americanwarshipbeforebeing transferred

to the Kaiyo Maru mfl

V-,L.A mockingrhymein Edo clearlylabeled hima coward: 'He came back in

flight,afraid to fight,leaving his men behind.'15On the other hand, Edo

commonerswere hardlysympatheticwith the imperialcause. One satirical

cartoonsold on thestreetsof thecityin thespringof 1868ascribedtheimperial

victoryat Toba-Fushimito superiorfartingpower.

Immediatelyfollowingthedefeatof theTokugawa forcesat Toba-Fushimi,

an imperialdecreechargedKeiki withtreasonand urgedan immediateattack

upon his domains. A forceof some 50,000 men leftKyoto on 2.11. It made

rapid progressand by 3.5 the main forcehad reached Sumpu Castle, where

headquarterswereestablishedforthe finalstagesof the siege on Edo.

Excitementamong the people of Edo increasedas the imperialarmydrew

closer. It was difficult

to understandKeiki's policyof submission.On 2.11, the

same day thatimperialtroopsleftKyoto, Keiki announcedthathe was going

into domiciliaryconfinement

at Daiji-in ?2TS in the precinctsof Kan'eiji tI4

# at Ueno. The decision was not generallyliked; popular lampoons called

Keiki a coward and manyTokugawa troopschose to decamp. Katsu Kaishui,

Keiki's choice of mediatorwiththe imperialregimeand de factocommander

15

SokumenkanBakumatsu-shi,2, p. 776.

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Mon, 16 Nov 2015 21:47:14 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

134

Monumenta Nipponica, 45:2

of the Tokugawa military,was forcedto cope both withinstitutionalbreakdown and popular discontent.His diaryof 2.1 notes:

At presenta successionof boats filledwiththe troopsdefeatedat TobaFushimiis arriving

in Edo.... Theyare disgruntled

byshortages

of foodand

lackofshelter.

Moreover,

theyareangeredbyinsufficient

pay.Theyareforming

secretbandsand decamping.... The townsmen

are dailymoredistressed

and

suspicious.Officials

repeatedly

orderincreases

infinancial

contributions

without

specific

purposesin mind.... Evenifenemytroopsdo notcome,itwillnotbe

longbeforeEdo collapsesfromwithin.16

Troop desertions,pro-waragitation,threatsof assassination,werebut the

beginningof theproblemsKatsu and otherTokugawa authoritiesfacedduring

the earlymonthsof 1868. Maintainingpublic orderin Edo and the surrounding countrysidewas the greatestchallenge.As the imperialarmyadvanced

on Edo and existingTokugawa institutionsof governmentcollapsed, Edo

commonersand theircountrycousins became increasingly

insecure.Peasant

riotingin the villagessurroundingEdo reacheda peak duringthistime,adding to an overridingsense of doom withinthe city.

The citycommissionersissued decreeafterdecreein an attemptto restorea

sense of security.Katsu also sanctionedthe use of bands of pro-Tokugawa

activistsin peacekeepingfunctions.The attemptwas to kill two birds with

one stone:to restorepublicorderin Edo and thesurrounding

and

countryside,

to assertcontrolover potentialsources of insurrection.To this end, Kondo

Isami's B% Shinchogumi,renamedthe ChimbutaiA ,_ or 'Pacification

Squad', was sentintotheMusashi and Kozuke regionswithordersto suppress

peasant rioting.WithinEdo, membersof the Shogitaiwereorderedto patrol

the streetsat night.

These measuresproved unsuccessful.Thieves and bullieshad virtualcommand of the citystreets.The Tokugawa police forcewas powerless;whenthe

imperialcommandoccupied Edo earlyin the 4thMonth,it had been reduced

to a mereforty-two

men.17 As Katsu confidedin his diary:

inEdo, beginning

withthevariousdaimyoandhatamoto

Recently

residences,

people are in the streetsnightand day cartingtheirbelongings

out to the

As a resultseveralthousandpeopleare rushing

countryside.

about,as though

at a fire,payingno heedto laws,howeverrepeatedly

theymaybe issued.For

the mostpart,hatamotoare returning

to theirestatesor hidingout in the

close to Edo. Takingadvantageof the situation,robbershave

countryside

18

and are stealingvaluablesand molesting

appearedeverywhere

women.

16 KKZ, 19, p. 12.

17 Tokyo Hyakunen-shi

HenshuiIinkai,ed.,

Tokyo Hyakunen-shi,

1973-1984, 2, p. 39.

18 KKZ,

19, p. 36.

Tokyo-to,

This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Mon, 16 Nov 2015 21:47:14 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Download edo in 1868 (1)

edo_in_1868 (1).pdf (PDF, 5.52 MB)

Download PDF

Share this file on social networks

Link to this page

Permanent link

Use the permanent link to the download page to share your document on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or directly with a contact by e-Mail, Messenger, Whatsapp, Line..

Short link

Use the short link to share your document on Twitter or by text message (SMS)

HTML Code

Copy the following HTML code to share your document on a Website or Blog

QR Code to this page

This file has been shared publicly by a user of PDF Archive.

Document ID: 0000315533.