Roderick Heath 2019 Film Writing (PDF)

File information

This has been sent on pdf-archive.com on 25/12/2019 at 06:54, from IP address 122.149.x.x.

The current document download page has been viewed 778 times.

File size: 1.32 MB (809 pages).

Privacy: public file

File preview

roderick heath

film writing

2019

featuring writing for the websites

film freedonia

this island rod

wonders in the dark

© Text by Roderick D. Heath 2019

All Rights Reserved

Contents

Title

The Mark of Zorro (1940)

RoboCop (1987)

The Trip (1967)

Zorba the Greek (1964)

Tempting Devils (2018)

Suspiria (2018)

Zulu (1964)

Oedipus Rex (1957)

The Godfather (1972) / The Godfather

Part II (1974) / The Godfather Part III

(1990)

Saturn 3 (1980)

The Birth of Japan (1958)

Captain Marvel (2019)

The Runaways (2010)

Score (1974)

Mortal Engines (2018)

Alexander The Great (1956)

Reservoir Dogs (1992)

Us (2019)

The Wandering Earth (2019)

The Matrix (1999) / The Matrix

Reloaded (2003) / The Matrix

Revolutions (2003)

Avengers: Endgame (2019)

The Manitou (1978)

The Story of Dr. Wassell (1944)

The Devil Commands (1941)

Night Moves (1975)

The Island (1980)

Victory (1919)

Godzilla, King of the Monsters (2019)

Cabiria (1914)

The Last Run (1971)

Airplane! (1980) / Top Secret! (1984)

Domino (2019)

Johnny Angel (1945)

Long Day’s Journey Into Night (2018)

Page

3

13

32

42

60

68

78

90

96

136

147

159

167

176

186

193

205

222

231

234

250

258

265

282

289

307

314

323

330

347

355

375

383

392

Title

Twister (1996)

Intolerance: Love’s Struggle

Throughout the Ages (1916)

La Pointe-Courte (1954)

Only Angels Have Wings (1939) /

Hatari! (1963)

Mesa of Lost Women (1953)

The Parallax View (1973)

The Ambulance (1990)

The FBI Story (1959)

Once Upon A Time…In Hollywood

(2019)

Crawl (2019)

The Souvenir (2019)

The Riddle of the Sands (1979)

J’accuse (1919)

Ad Astra (2019)

Rambo: Last Blood (2019)

Peeping Tom (1960)

The Blob (1988)

The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967)

Joker (2019)

Son of Dracula (1943)

Black Cat Mansion (1958) / The Ghost

of Yotsuya (1959)

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

/ Invasion of the Body Snatchers

(1978)

Terminator: Dark Fate (2019)

The Wicked Lady (1945)

Ford v Ferrari (2019)

Knives Out (2019)

The Irishman (2019)

Star Wars – Episode IX: The Rise of

Skywalker (2019)

1917 (2019)

25 Essential Films of the 2010s

Page

408

415

435

445

467

476

490

500

511

527

532

550

557

575

588

595

616

626

640

654

672

688

711

718

730

741

751

773

785

791

The Mark of Zorro (1940)

this island rod, 12 January

Rouben Mamoulian isn‘t so well-respected today considering he was seen as one of the most vital and

innovative directors of the early sound era by his contemporaries. That reputation was established with

films like Applause (1929), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), and Love Me Tonight (1932), with his

readiness to strain against the technical limitations of the fledging format and gild his movies with real

formal creativity and lustre, from the aggressively mobile camerawork he deployed in Applause to the

ingenious and endlessly influential use of choreographed sound and motion in Love Me Tonight, and the

coded sexuality and pictorial force of Queen Christina (1933). Part of his lapsed reputation can be put

down to his very patchy later career, which often saw him sacked from or quitting a range of prestigious

productions including Laura (1944), Porgy and Bess (1959), and Cleopatra (1963), and his return to

directing for the stage, where he had first made his name. Mamoulian, born in Armenia, had progressed

westwards in theatre work and found success directing on Broadway. He debuted as a filmmaker

with Applause and eventually was given the fateful job of directing the first-ever Technicolor film, Becky

Sharp, in 1935. The Mark of Zorro, a remake of the 1920 Douglas Fairbanks film based in turn on

Johnston McCulley‘s The Curse of Capistrano, was the first of two vehicles Mamoulian made with Tyrone

Power at Twentieth Century Fox, then quickly rising to the top of the Hollywood heap; the follow-up

was Blood and Sand (1941). On both films Mamoulian unleashed his lushest visuals, entering entirely into

a folk-memory zone of Latin mystique.

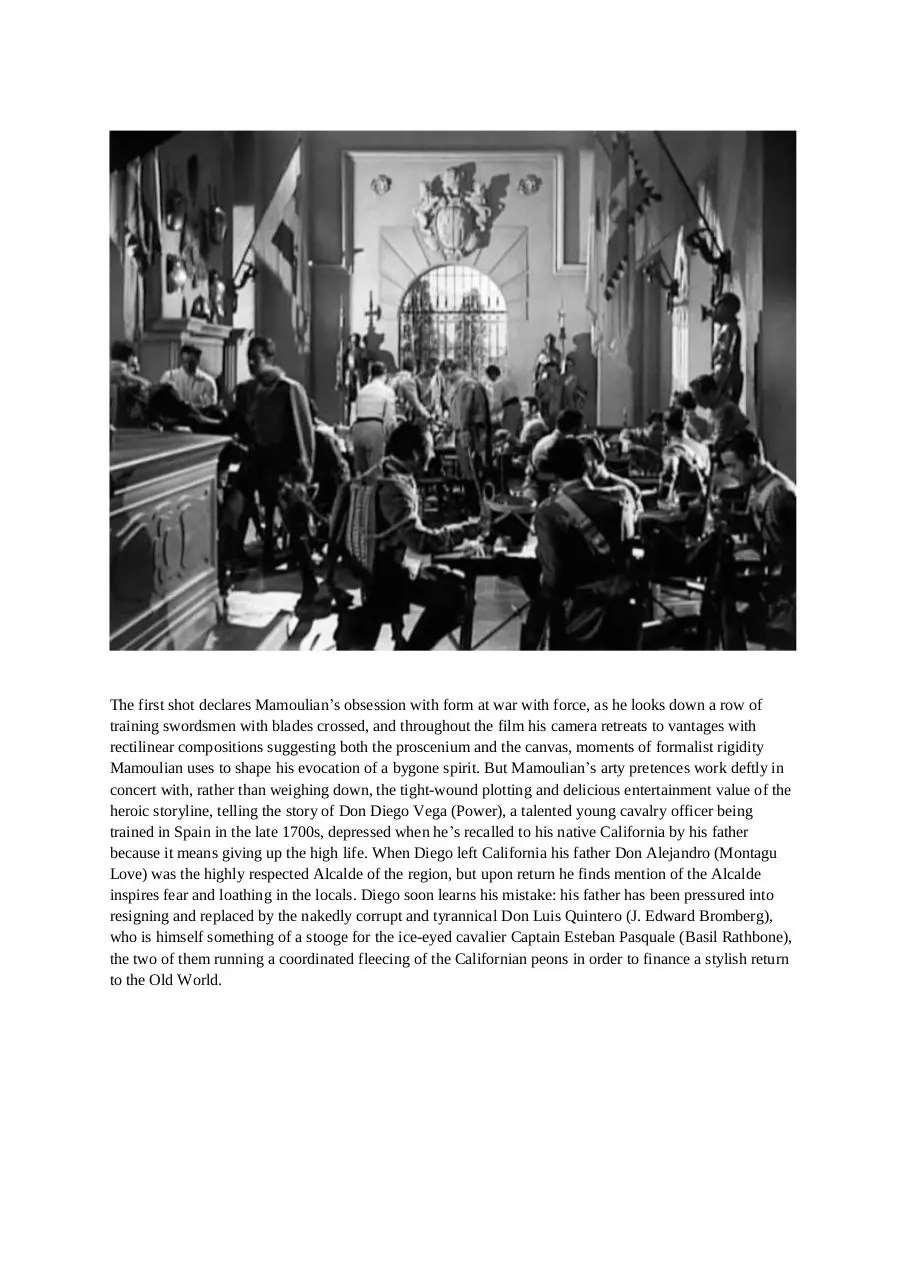

The first shot declares Mamoulian‘s obsession with form at war with force, as he looks down a row of

training swordsmen with blades crossed, and throughout the film his camera retreats to vantages with

rectilinear compositions suggesting both the proscenium and the canvas, moments of formalist rigidity

Mamoulian uses to shape his evocation of a bygone spirit. But Mamoulian‘s arty pretences work deftly in

concert with, rather than weighing down, the tight-wound plotting and delicious entertainment value of the

heroic storyline, telling the story of Don Diego Vega (Power), a talented young cavalry officer being

trained in Spain in the late 1700s, depressed when he‘s recalled to his native California by his father

because it means giving up the high life. When Diego left California his father Don Alejandro (Montagu

Love) was the highly respected Alcalde of the region, but upon return he finds mention of the Alcalde

inspires fear and loathing in the locals. Diego soon learns his mistake: his father has been pressured into

resigning and replaced by the nakedly corrupt and tyrannical Don Luis Quintero (J. Edward Bromberg),

who is himself something of a stooge for the ice-eyed cavalier Captain Esteban Pasquale (Basil Rathbone),

the two of them running a coordinated fleecing of the Californian peons in order to finance a stylish return

to the Old World.

Comprehending the new situation, Diego adopts an air of mincing detachment, playing the fey and worldweary courtier. He even extends the act when talking with his father and his childhood mentor Friar Felipe

(Eugene Pallette), much to their infuriation, because Diego feels his father‘s reverence for legal forms

demands he work around him, and so must be deceived just as much as the enemy. Diego ventures out into

the night swathed in black performing acts of banditry and rebellion under the name of Zorro, whilst

insinuating himself into Quintero‘s household with his preening act. Quintero‘s wife Inez (Gale

Sondergaard) encourages her husband‘s greed as she wants to make a splash at the Spanish court and be

the object of male attention. She gleefully lays claim to Diego as a taster‘s choice for that exalted end, but

he falls utterly under the spell of the Quinteros‘ ward and niece Lolita (Linda Darnell), who in turn thinks

he‘s a terrible person and instead pines for the brave and exotic Zorro, who she helps save one night when

he threatens her uncle in his palace and then tries to elude searchers by dressing a monk.

Not as grandly scaled or expansively staged as Warner Bros. Errol Flynn vehicles like The Adventures of

Robin Hood (1938), or as piningly intimate and romantic as The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934), both of which it

assimilates, The Mark of Zorro is nonetheless a tremendously entertaining and brilliantly compressed

package, with Mamoulian exploiting the relatively restrained production values for overtly artificial beauty

and requisite thrills, producing what could be the best-directed film in this style. I‘ve always particularly

enjoyed the uncommon backdrop of colonial California that distinguishes the Zorro mythology, with its

faintly surreal atmosphere of Imperial Spanish gentility and rigidity grafted onto a raw and dusty land, and

Mamoulian presents an entirely stylised version of this allure. Mamoulian speeds through the familiar

business for both the Zorro character and the genre, although he doesn‘t pretend to be terribly interested in

the period class politics and political machinations (although this could also be Mamoulian‘s masters at

Fox proving timid in the face of annexing Warner‘s hardy grip on the class-conscious melodrama). The

film offers rather crisp action staging, good-humoured love scenes, and a great feel for the energy and

physical spectacle of his actors.

That‘s easy when he‘s got stars as good-looking as Power, Rathbone, and Darnell, who, astonishingly, was

only 17 at the time. Long before Power took on the anxious and harried look he had in middle age as his

heart problem worsened, Mamoulian expertly located his capacity for deft self-satire in playing both the

ruefully intense and archly virile Diego and his alter ego as a vain and effeminate charmer, who disarms

his foes but ironically sharpens points of antagonism in other ways. Pasquale, a talented roué (he was

chased out of Spain after romancing the wrong man‘s wife), glares rapiers at Diego as Inez falls under his

spell when Pasquale‘s already having an affair with her. Much of the film‘s clandestine impetus comes not

from swordsmanship and political ferment but from the rivalry of aunt and niece, as Inez wants to fling in

a convent to remove her erotic competition, with Diego the mutual fetish totem. Queer subtext becomes

just plain text with a jolt of real force as Diego in full-on fop mode notes Pasquale vengefully lancing his

dessert: ―You seem to regard that poor fruit as an enemy.‖

The Mark of Zorro takes the undertones of romantic disaffection and covert sexual ambiguity explored

in The Scarlet Pimpernel, and sublimates them into an ongoing game of attraction and rebuff that unfolds

on both the romantic and political levels. Power and Darnell perform a passo doble in increasingly ardent

lockstep whilst maintaining aspects of glazed and haughty disinterest to set the seal on what Diego wants

the Quinteros to think is a marriage of political convenience. Meanwhile Diego‘s father is outraged his son

can romance his enemy‘s daughter. Takes on the Zorro mythos have long tended to exploit the theme of

role-playing and revelation in a way most its conceptual children – the Lone Ranger, the Shadow, Batman

– never brought themselves to do, in part because Zorro as a character has a romantic intensity none of his

followers have. Diego and Lolita‘s first meeting sees Diego-as-Zorro-as-monk accidentally making

constant slips of the tongue in praise of Lolita‘s comely form and declares she‘d be doing God more good

as a producer of upstanding young Christians than as a nun. Lolita, realising who the imposter is, protects

him from searching soldiers, cueing Diego kissing her hand with grateful passion – a great example of

Mamoulian‘s talent for turning the tone from droll to fervent on a dime.

Of course, there‘s also plenty of robbing, gunfighting, swordfighting, horse riding, eluding and tormenting

the forces of oppressive authority, and scratching ‗Z‘ in wood and cloth and stone. Zorro‘s identity is soon

revealed to the Friar, whose aid Diego seeks in wealth redistribution, and to Lolita herself, necessitated

when Diego comes to visit her in his Zorro disguise but has to cast it off to avoid being found out by

Pasquale. Lolita is too smitten with him, and too disapproving of her bitchy relatives, to blow the whistle

on him. Quintero‘s status as chief villain is mostly belied by his largely comedic function as a malleable

robber baron, contrasting Rathbone‘s tougher foe. Rathbone‘s face was so perfect for this kind of role

because he looked like a portrait of old world nobility slightly warped by a proto-modernist‘s eye, noting

depravity and ruthless intelligence and an aspect of the vulture in his eyes and long nose. The cruel

enforcer ultimately proves a touch less canny than the timorous oppressor, as Pasquale lets himself be

baited into a duel with Diego and immediately finds himself in a fight where neither knows the outcome,

whilst Quintero watches and waits to move on the winner.

The duel scene coins one of the classic gags of swashbuckler cinema, as Diego slashes through a candle so

cleanly it doesn‘t topple, before the real fight starts, a truly amazing feat of skill and concerted energy from

Power and Rathbone. This scene also gains much of its charge and sense of physical dynamism not by

unleashing the actors in great, echoing halls but in a tight and claustrophobic office, where the moves and

displays of physicality have to negotiate the furniture and fixtures; the combination makes the fight seem

all the more feral and violent, before inevitably Diego manages to skewer Pasquale, dislodging a print

covering one his scratched Z calling-cards, as if accidentally signing his handiwork. Prior to this scene,

there‘s the brief but stirring sight of Palette and Rathbone fencing, with the rotund supporting actor

displaying surprising talent for the art.

Nearly every frame of The Mark of Zorro looks like a purposeful pastiche of some classical Spanish

painter. Flower-bedecked tendrils glow against shadows. Ranks of musicians and siesta-taking peasants

gather in sculptural postures amidst lances of source lighting. Darnell, swathed in black lace and mantilla,

cowers before an icon with glowing candles before turning to Power in cowl amidst a dance of light and

dark, piety and sex appeal. Zorro bailing up Pasquale and other government troops, avenger from the night

appearing in a composition as carefully composed as anything presented a belle époque salon. Scrambling

cavalry men pouring out into the night, one of many shots that embrace both painterly stillness and

tumultuous movement, including the very last shot, celebrating restored order. This comes only after the

traditional mass battle, as Diego manages to escape with a rather paltry ruse and rouse the populace to aid

the Dons in deposing Quintero, father and son fighting side by side before the proper business of mating

can start in earnest, Diego‘s sword finally lodged right where it belongs, deep in the frame of the family

hacienda. Henry King would work with Power and augment the campy aspect of this for The Black

Swan (1942) and the earnest side for Captain From Castile, whilst 1996‘s The Mask of Zorro is both

Martin Campbell‘s sequel and remake.

RoboCop (1987)

film freedonia, 14 January

Director: Paul Verhoeven

Screenwriter: Michael Miner, Ed Neumeier

Like many a filmmaker who, having gained stature and plaudits in their native land, heard the siren call of

new shores, fresh stories, and better paydays, Paul Verhoeven vacated his place as the most lauded director

in the Netherlands to fight for a place on the totem pole in Hollywood. His first film there, the medieval

adventure Flesh + Blood (1985), hardly stirred a ripple, but the title was to prove a veritable mission

statement for the way Verhoeven would heartily embrace a new career by pushing it to the max.

Verhoeven‘s lack of timidity as a Hollywood director who notably refused to deal in the usual pretences

expected of transplanted auteurs was hardly surprising in light of the movies he had made in the

Netherlands. Their number included his sex farce debut Wat Zien Ik (1972), about a prostitute‘s

misadventures, Turkish Delight (1974), his spectacularly vulgar take on the romantic tragicomedy, and his

fetid, delirious melange of horror film, erotica, and metaphysical angst, The Fourth Man (1983). He had

offered some films of more restrained temperament, including the historical class-clash epic Keetje

Tippel (1975) and the Oscar-winning war film Soldier of Orange (1977). But something in Verhoeven‘s

overheated sensibility couldn‘t be contained too long by such relatively straight-laced fare.

So when he went Hollywood, Verhoeven went big. Where Hollywood executives told him the audience

wanted sex and violence, he would serve double portions, as part of an outlandish mixture of often gross

mockery, earnest melodrama, and sleight of hand in tackling Verhoeven‘s deeper interest in the politics of

body and soul. He didn‘t appreciate Ed Neumeier and Michael Miner‘s script for RoboCop when he first

read it, but his wife did, pointing out to him the barbed skepticism aimed at the emerging corporate

dominance, and the theme of the Christ-like saviour. The film was destined to be a smash hit and would

place Verhoeven on top for a time until he pushed his tendencies just a little too far for critics and

audiences alike. But RoboCop, perhaps his greatest film and a remarkable balancing act by any measure,

has never lost its cachet as a cult film sprung out of most surprising soil, standing alongside The

Terminator (1984), Aliens (1986), and Predator (1987) in the holy sepulchre of ‗80s sci-fi action but also

outstripping them in the force and clarity of its ideas and provocations. Great science fiction is usually part

imagination, part reportage, with the best extrapolating trends of the moment of conception and projecting

them into a fictional future that if done well can retain that seer-like mystique.

Like many other movie-mad kids I watched the movie into the ground back when, and like many such

relics of a misspent youth it tends to sit around, a must-own for the movie collection but also a little like

part of the furniture. RoboCop hasn‘t lost its pure, grade-A Columbian potency or its scabrously funny,

cruelly satirical purview. Nonetheless time has changed how I relate to the movie: the general mayhem and

specific blend of idealism and cynicism, so perfectly in synch with a teenage mindset, gives way to a

deeper empathy for hero Alex Murphy, a family man torn away from identity and family – what does age

do, but make us feel like pieces are being cut off us and remaking us into hardened things we don‘t quite

recognise, whilst stealing away things we love? RoboCop‘s prognosticative edge seems near limitless,

anticipating contemporary concerns of automation and artificial intelligence, the loss of public sovereignty

over our institutions, the debasement of social discourse and the media, the unhinged power granted

corporations in our lives and the grim spectre of government being annexed by businesspeople – all

wrapped up in RoboCop‘s shiny, sardonic shell. Even some of the film‘s more dated references, like jokes

related to Ronald Reagan‘s Star Wars project, have gained a new window of relevance, whilst others, like

the indictment of a city like Detroit being first built and then trashed and then gentrified at the expense of

the inhabitants according to the whims of capitalism, never stopped being immediate.

Over and above its satirical aspect, RoboCop is of course also a gloriously unhinged pulp adventure that

finds whacked-out poetry in the notion of a normal man, his body appropriated for corporate use,

transformed into a Kevlar-coated knight. RoboCop‘s insidious genius is immediately signalled by the use

of TV news reports and ads to frame the action, Greek chorus gone smarmy and commercial: the cold

opening offers Media Break, a news programme that takes the pattern of news reduced to capsules and

soundbites to an extreme – ―You give us three minutes and we‘ll give you the world!‖ – filled with biting

bits of futuristic geopolitical info, like the apartheid South African gone belligerent and nuclear, and the

―Star Wars Orbiting Peace Platform‖ that fouls up, at first comically and then scorching a section of

California to a cinder. This device also lets Verhoeven summarise the film‘s basic plot and background

with sublime efficiency. Interspersed are fake ads, grounding futuristic phenomena in familiar packaging,

like one for mechanical heart transplants, and sketching out a future society where the phenomena of all

kinds – human, machine, news, marketing – are dissolving into a grotesque and lawless stew. On to the

real show: the setting is a futuristic Detroit where the infrastructure of the working class‘s livelihoods has

been reduced to cavernous shells whilst a new elite of corporate overlords rule on high.

A massive corporation with the delightful nonentity name of Omni Consumer Products, or OCP, has taken

over the privatised police force of Detroit, a city that has degenerated into a rundown, crime-infested,

Hobbesian hellhole. The cops are outmatched by criminals toting heavy weaponry also made by OCP who

manufacture military arms, and the police are slowly being starved of resources by their new masters.

OCP‘s barely hidden agenda is to rebuild Detroit into the new and shiny Delta City, whilst also hoping to

replace the human police with robotic workers, cheaper, easier to maintain, and utterly unquestioning of

authority. This project hits a speed bump however, when OCP‘s number two man Dick Jones (Ronny Cox)

parades the product of his R&D lab before the company board and the company chairman, referred to only

as ―The Old Man‖ (Dan O‘Herlihy). The hulking, prototype robotic law enforcer ED-209 machine guns

unfortunate executive Kinney (Kevin Page) to a bloody pulp during a simulated exercise to demonstrate its

abilities. Mid-grade executive Bob Morton (Miguel Ferrer), assigned to develop contingency projects in

case of the ED-209‘s failure to perform, steams in to steal Jones‘s thunder and capture the Old Man‘s

interest with his alternative: his notion is to create a cyborg incorporating the brain and know-how of a real

policeman.

Morton is already busy trying to orchestrate the ready providing of a good test subject, by restructuring the

police force and putting good candidates into dangerous positions. One such candidate, Alex Murphy

(Peter Weller), arrives for duty at Detroit‘s most hazardous precinct, and is partnered up the station‘s hardass commander Sgt Reed (Robert DoQui) with the equally tough Officer Anne Lewis (Nancy Allen). The

partners soon swing into action, chasing down a team of bank robbers commanded by the malevolent and

ambitious Clarence Boddicker (Kurtwood Smith), and pursue them to an abandoned steel mill. There,

Lewis is knocked out and Murphy, after gunning down one of the crew, is bailed up by the rest and used

for target practice by the gang, before Boddicker gives him a coup-de-grace in the head. Rushed to

hospital, the medical team can‘t save Murphy‘s life, but his organic remains become the indispensible

central component in Morton‘s exercise in Frankensteinian public utility service.

The savage boardroom sequence offers startling violence amidst arch mockery of corporate culture that has

strong overtones of mirthful lampoons from days past like Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1956)

and How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying (1967), where young go-getters try to impress the

man upstairs with wacky notions. The Old Man gives a speech of hollow self-congratulations met with

applause, particularly from the eagerly brownnosing Morton, and hides his face in shame after Jones‘

hiccup before admonishing him oh so solemnly, ―Dick, I‘m very disappointed.‖ The conceptual starting

point is the same as Brett Easton Ellis‘ American Psycho as the corporate world is revealed to be an arena

of literal life-and-death competition, replete with cocaine orgies and blood-spattered exercises in free

enterprise from these upstanding captains of industry, but it‘s also a zone of slapstick absurdity, as the Old

Man cradles his head in cringing embarrassment in the face of Kinney‘s demise. ―We steal money to buy

coke and sell the coke and make even more money,‖ says Boddicker‘s lieutenant Emil (Paul McCrane),

which he holds as basic business acumen, and Boddicker and crew attempt a hostile takeover of a mob

drug business.

Street-level capitalism is soon revealed to be working in harmony with the glass citadels of corporatism,

for Boddicker works under the protection of Jones, who offers him the rights to control all the crime

proceeds in Delta City. ―Good business is where you find it,‖ Jones and Boddicker both parrot, one of the

many catchphrases that recur throughout the film, way-stations of commercialist mind colonisation:

everyone in the film, well before Robocop first marches out to battle, is already brainwashed to a certain

extent. Glimpses of television in this future are either ads, chop-chop news, or bawdy, soft-porn sitcoms,

disgorging another catchphrase, ―I‘ll buy that for a dollar!‖ Not, of course, that RoboCop was so unique in

terms of its targets when it was released. Corporate honchos, snotty yuppies, and government heavies were

kicked about in quite a few ‗80s action films, victims of a lingering suspicion of authority, a hangover in

genre film reflexes from the counterculture era but gaining a more blue collar basis in the era of the

common man (a couple of years later, in Leviathan, 1989, for instance, a female corporate boss gets a sock

in the face from Weller, playing one of the workers she left to die).

What makes RoboCop so striking in this regard is the way it coherently envisions its future world. The

threat of collapse into anarchy is both imminent but also manufactured. The Old Man crows about changes

to taxation that have allowed corporate growth at the price of running down civic infrastructure, to which

the proposed cure-all is corporate governance. Meanwhile the assailed, under-resourced, cost-ineffective

police are driven to the point of considering a strike, something Reed considers utterly verboten. RoboCop

is a product intended, like ED-209, to render messy human components to the system unnecessary. And

yet Morton‘s idea needs the human element. RoboCop‘s near-future has hues of dystopia and the shining

prospects of renewal on the horizon seem to promise only new dimensions in iniquity. In terms of the

science fiction genre in general and in more specific conceptual terms, the entire narrative can be seen as

the stage before the construction of the great city of Metropolis (1926).

In this landscape Murphy is a plain anachronism, a competent cop with a sturdy home life and an oldschool delight in the mystique of the western hero, recreating the signature gun-spinning move of his

young son‘s favourite TV character, T.J. Lazer, protagonist of a sci-fi western blend, and admitting to

Lewis that ―I get a kick out of it.‖ Rebirth as RoboCop ironically remakes the gunslinger as futuristic hero,

but as a 21st century myth, or at least a 1980s anticipation of one, the context is infinitely more questioning

about the actual meaning of such heroism – what was the Old West hero but precursor and defender of

more efficient exploitation of the land? RoboCop depicts the search for freedom in immediate and

gruelling detail, perceiving the entire world, never mind the computer chips and LED screen that feed

fragments of corporate circumspection to Murphy, as a trap of conspiring paradigms. It doesn‘t seem at all

coincidental that Jones and Boddicker‘s association closely resembles that of Frank and Morton in Once

Upon a Time in the West (1968), hired gun and business potentate learning from each-other with mutual

yearnings to be the other. The true cleverness of RoboCop, and the source of its power, lies in Verhoeven

and the screenwriters‘ precise feel for what to make sport of and what to take seriously, playing their hero

and the other cops absolutely straight. This approach allowed Verhoeven to extend his obsession with the

mysterious blurring of the sacred and profane to emblematic extremes.

Verhoeven‘s visual patterns constantly stress the act of seeing, experiencing, processing, and also the

limitations imposed upon them. Verhoeven repeatedly returns to Media Brief bulletins and commercials

without warning, assaulting the demarcations between standard movie narrative and meta-commentary,

between movie-watching as self-evident flow and self-critical process. Point-of-view shots are a constant

motif. These kind of shots were increasingly common in this brand of ‗80s sci-fi action movie, the reddrenched viewpoint of the Terminator, the infrared gaudiness of the Predator, evoking new ways of seeing

the world through technological media. Verhoeven renders them more purposeful in terms of his hero‘s

experience. He obliges the audience to spend much time watching this world through Murphy-RoboCop‘s

eyes, or from those who look on at him with blends of heartache and fear. Murphy‘s death and resurrection

are first-person events, his viewpoint maintained as doctors try to save his life, in alternation with

incredible close-ups of Weller‘s glassy blue eyes. Flashback memories take on dimensions of spiritual

symbolism, the sight of his wife and son waving to him from the driveway of his house as he drives away

becoming a more permanent and piercingly wistful evocation of loss.

Murphy‘s transformation into RoboCop continues in this vein, experience reduced to brief snatches of

online awareness, enough time to observe his creation team and overseers like Morton in all their crass and

clumsy humanity. RoboCop is supposed to be a completely pliable tool, without memory or sense of self,

only a series of simple and unswaying directives to guide his actions. As Murphy-RoboCop rises from his

seat to the applause of the technicians and executives, his vision is pixelated by video feed and crisscrossed by targeting grids and computer read-outs, with a viewpoint that‘s rigorously linear and

straightforward, Verhoeven‘s subtle jab at the drab functionality of much Hollywood filmmaking. But

dream and memory come to disrupt the way of seeing OCP impose upon him, making the film, in its way,

a new paradigm for the classic surrealist creed. Verhoeven cleverly extends the feeling of displacement

and the shock of the new as the cops dash through the halls of their precinct trying to catch a glimpse of

the outlandish newcomer in their midst, a gleaming hunk of technological force, a masculinised answer to

the sleek robot Maria of Metropolis. One of the most logical throwaway details also contains one of its

sharpest gags, as RoboCop has to consume a paste close to baby food to keep his organic parts alive,

humanity at last perfectly infantilised and rationalised. The film found a way to weaponise David

Cronenberg‘s dank dreams of body perversion and intrusion.

RoboCop is sent out to snare the bad guys – one of Verhoeven‘s many circular motifs suggests something

of Murphy‘s spirit is still within RoboCop as he drives out of the precinct car park with sparks in his wake

on the steep ramp. Verhoeven compresses vignettes of totemic pop vigilantism into gems of black comedy

here, as he offers several hilariously hyperbolic versions of the kinds of street crimes reported breathlessly

on nightly news and in cheesy movies. A stick-up man with a machine gun terrorising a market. A pair of

denim-clad rapists. Disgruntled former councillor Ron Miller (Mark Carlton) holding the mayor hostage.

The stick-up man is easily sent flying into a refrigerator as his bullets ricochet off RoboCop‘s armour.

More wit is required to take down the rapists: RoboCop successfully shoots between their victim‘s legs to

make mincemeat of an offending member. The hostage-taker is dragged through a wall and punched out a

window (one of my favourite parts of the film is the terrorist‘s list of demands to the negotiating cop

outside, including fresh coffee, his job back, and a new car, and the cop‘s assurance: ―Let the Mayor go

and we‘ll even throw in a Blaupunkt.‖) So successful are RoboCop‘s forays that Morton‘s hubris becomes

outsized, crowing to the media that crime will be wiped out in 90 days and dissing Jones in the executive

washroom at OCP without realising the target himself is in a toilet stall. Morton is soon assured he‘s truly

earned an enemy, but doesn‘t quite realised how dangerous an enemy until Boddicker barges his way into

Morton‘s house, shoots him in the legs, and leaves him to watch a DVD of Jones gloating as a bomb ticks

down to zero.

Just prior to getting his goose cooked, Verhoeven gleefully portrays Morton and a pair of models indulging

lashings of snow white and fetid sexuality, in a scene that feels eminently like the filmmakers probably

witnessed such a scene or perhaps even indulged it somewhere in the Hollywood hills: ―God I love to be

with intelligent women,‖ Morton crows to the dimwit pair before snorting coke off one‘s tits, summarising

the mindset of the executive sexist with cruel exactitude. Boddicker and his crew, by contrast to the

corporate corsairs, are a multiracial bunch of scumbags and overgrown school bullies who enjoy turmoil

and tormenting, evinced as they sadistically blow pieces off Murphy, and later Emil threatens a geeky gas

station worker (―Are you some kind of college boy?…Think you can outsmart a bullet?‖). They‘re logical

end-products of a society based around dumbing things down and celebrating ruthless muscle. That

process is in itself a product of the torturing dualism that Verhoeven constantly perceives in the human

condition. People at the pinnacle want the seamy pleasure those as the bottom can give them; those at the

bottom wish to drag everything down but then ascend in its place. By the time the cops do actually strike

and leave the streets to the marauders, the crew unleash their casual destructive impulses with an impunity

reminiscent of Verhoeven‘s antihero in Turkish Delight, a madcap incarnation of impulse and basic

organic hunger detached from all natural feeling for higher function, as well as the ensnared bisexual

protagonist of The Fourth Man, who finds himself trapped between sweat-inducing desire and beckoning

transcendence.

Murphy meanwhile experiences the return of consciousness as a digital glitch, the face of his killer leering

at him in fuzzy dream, wrenching him out of repose and driving him out into the night, with Lewis‘

attempt to reach the man within – ―Murphy, it‘s you!‖ – ringing in his ears. Encountering Emil as he robs

the gas station, mutual recognition spooks both men, and the device of recognition is, of course, a

catchphrase: Murphy‘s favourite quip, perhaps also culled from T.J. Lazer, ―Dead or alive, you‘re coming

with me.‖ Some of the film‘s funniest jokes are also its least subtle, like the constant repetitions of the

diminutive of Jones‘ first name, and the key object of consumerist fancy, the 6000-SUX sports car, a car

that fulfils the dream of conspicuous consumption – it nicely meets Miller‘s criteria for his dream car that

it give ―really shitty gas mileage.‖ Verhoeven returns to the first-person style as Murphy for an amazing

sequence where his trash satire and poetic sense of elusive memory work in perfect tandem, following the

breadcrumb trail back through Emil‘s arrest record through to what used to be his home. Here he finds a

smarmy salesman guiding him through his house on video screens, reducing the setting of his life to a

series of metrics and brand names, whilst the ghostly memories of his wife (Angie Bolling) and son (Jason

Levine) loom before him, conjured out of the past and dissolving again. Murphy, in his prowling distress,

punches in one of the salesman video screens, the first overt act of revolt against the overwhelming web of

choking commercialism and phony pleasantry glimpsed throughout the film. Characteristically, Verhoeven

eases back from the emotional crescendo with a return to comedy whilst still managing to step up the

narrative pace as he makes a crash-cut to a nightclub, as Murphy hunts down another of Boddicker‘s

associates, Leon (Ray Wise). Leon tries to kick the cyborg in the balls but of course gets only some broken

toes for his pains and the dancing denizens hoot in approval as Murphy drags Leon out by his hair.

One of Verhoeven‘s master strokes was in casting, putting actors in vividly counter-intuitive roles, like

casting the eternally girlish Allen as a tough cop, Cox, best known before this as the dreamiest member of

the rowing foursome in Deliverance (1972), as a raging, strutting prick, and Smith, who mostly had played

cops in various TV shows before this, as a brutal bandit king, utilising his aura of intelligent authority with

an extra layer of antisocial acidity, converting all his lines into little arias of cruel humour. Weller had been

circling the edges of stardom for a few years before being cast as Murphy, in cultish fare like Of Unknown

Origin (1983), in which he played an everyman doing battle with a giant rat, and the title role

of Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the Eighth Dimension (1984), where he played a polymath pulp

hero; the diversity of such parts signalled both Weller‘s skill as an actor and also his peculiar

physiognomy, spindly, slightly hangdog, but equipped with soulful eyes and cupid lips. The latter feature

being just about all you can see of him throughout RoboCop and so vital to his presence, some remnant of

the human, the romantic, amidst the technocratic fantasia. Weller‘s ingenuity as an actor is vital to

selling RoboCop, in the mechanical gait of the character, the way he seems to struggle against his new

form and then to use it effectively express his rage and distress as he begins to regain his memory.

Somehow he manages to make all the stages of his role effectively expressive – from the all-too-vulnerable

Murphy to the grimly stoic cyborg to the blank, haunted, quietly resolved remnant that emerges towards

the end.

Murphy‘s crashing of a business meeting between Boddicker and a drug kingpin (Lee DeBroux) sees him

wipe out a small army of hoodlums, and bash Boddicker around until he tries to warn off Murphy by

telling him Jones looks after him, but it‘s rather the reminder that Murphy is a cop that saves Boddicker‘s

life. Instead he casts him to Reed and heads off to arrest Jones, but soon finds a wicked limitation placed

upon him – the incapacity to take action against an OCP employee, ingrained in his programming. In this

future there is quite literally one law for the rich and another for the rest. Murphy has to elude an ED-209

set upon him by Jones – fortunately, that monstrosity, in what feels like a grand joke aimed at decades

worth of impractical robots in movies, can‘t negotiate the stairs – and then is almost shredded by the

combined fire of ranks of cops called out to deal with the apparently rogue cyborg. Basil Poledouris‘

tremendous scoring reaches an apogee here in the grand yet mournful evocation of mecha-Christ crucified

over and over again. Lewis manages to snatch Murphy away and helps him self-repair and recuperate in

the same steel mill where he was first shot up, and Jones sends Boddicker and crew after him, equipped

with explosive shell-lobbing guns. Verhoeven, via Murphy and Lewis, dishes out nasty comeuppances to

the criminals, but with a seething overlay of perverse, Looney Tunes-esque comedy: Emil, immersed in the

contents of a well-labelled vat of toxic waste, is reduced to a grotesque mass of melting flesh before being

run down by Boddicker; Leon is blown to smithereens by Lewis just as he whoops in triumph after

trapping Murphy under some junk, and Boddicker gets skewered in the throat by Murphy‘s data plug when

he gets just a little too close to crow over his pinioned opponent, a deadly steel spike that also looks like an

installation art take on flipping the bird.

What holds RoboCop together is the conviction with which Verhoeven and Weller celebrate their heroes,

the cops both human and augmented, even as just about everything around them is revealed to be some sort

of sham. When Verhoeven would return to a similar blend of high cynicism and straight-laced thrills

on Starship Troopers (1997), a lot more people didn‘t, or wouldn‘t, get the joke even as Verhoeven

unsubtly clad his spacefaring warriors in Nazi-esque uniforms. Such a lapse that time around was due in

large part because Verhoeven offered no wriggle room between the fascist precepts of his future society

and the aims of the heroes obliged to live in it; on the contrary, the film unstintingly states that their

qualities and desires are rather exactly fulfilled and expiated by that society, and infers a similar dynamic

can seduce all of us. That quality in some ways makes Starship Troopers the more sophisticated and slyly

unsparing as a ransacking of genre film, but in another sense the lack of such tension foils it; it can‘t thrill

in the way RoboCop can, and so isn‘t as effectively two-faced. Murphy returns to OCP Headquarters to

handle unfinished business, blowing up the ED-209 with quick efficiency – somehow Tippet and the sound

effects team manage to turn the death reel of the decapitate robot, which collapses with a ratcheting click

of its wayward toes, into a hilarious moment – before bursting into the company boardroom to brand Jones

as a killer before the Old Man and all the other corporate sharks. But Murphy cannot fire, not until the Old

Man delivers the true assassination according to his world‘s values, by firing Jones as he holds a gun to his

head.

This conclusion offers rowdy, crowd-pleasing flourishes with a sarcasm so complete it circles right back

around to earnestness, as Morton‘s executive pal Johnson (Felton Perry) gives Murphy and thumbs-up, and

the Old Man slides back into western flick argot – ―Nice shootin‘ son.‖ The executives, like the audience

and Murphy himself, in the end desperately want and need the western hero to exist even when it

completely cuts against the grain of all logic. Similarly, Murphy‘s final, simple, smiling utterance of his

name carries enormous power precisely because of the farcicality, the grotesquery that surrounds him, and

the hilariousness of the context only sharpens the sting of Murphy‘s self-reclamation. RoboCop was such a

hit that inevitably it spawned sequels, but just how essential Verhoeven‘s touch had been, and how smart

Miner and Neumeir‘s writing had been, was soon confirmed. The first follow-up, Irvin

Kershner‘s RoboCop 2 (1990), proved a disastrous mess which just about everyone involved blamed

everyone else for, retreading most aspects of the original but this time with the foulness turned up full and

the stabs at humour and excitement utterly leaden. Weller refused to return for the third instalment,

released in 1993, helmed by Fred Dekker, so Robert John Burke was cast in the role instead. This time the

result swung too far in the other direction from the second entry, playing more like an extended TV pilot

with goofy humour and a broad approach. Still, it did actually manage to provide a worthier follow-up.

Jose Padilha‘s would-be thoughtful but actually merely verbose and heavy-footed remake from 2014 tried

to turn its own by-committee, brand-exploiting status into the very subject of its riff, but neglected

everything else, and simply reduced proceedings to a crying bore. Some prototypes, it turns out, just can‘t

be reproduced.

The Trip (1967)

this island rod, 20 january

The official topic is the drug culture crawling its way out of the bohemian shadows to infect the minds of

clean-cut young company men with cravings for expressive meaning and infest the landscape with random

blooms of psychedelia. The backdrop and subtext is New Wave Hollywood wriggling its way out of the

chrysalis spun by Roger Corman‘s safe harbour of post-studio era exploitation. After abortive attempts by

Corman‘s usual writing collaborator Charles B. Griffith to come to terms with the zeitgeist, alumnus Jack

Nicholson came to his sensei with the New Testament on groovy escapades up in the Hollywood Hills, and

the director colonises fertile new ground for drive-ins and grindhouses in a livewire promissory note of

psychedelic spectacle for the terminally unhip to imbibe from a distance. Corman had already worked with

star Peter Fonda on his Antigone in black leather, The Wild Angels (1966), his first big studio venture, and

Dennis Hopper came on board to lay down the blueprint for an industry meltdown a couple of years down

the line. Square Corman had to go into the desert with his actors to drop some acid to get into the vibe and

reported hallucinations of glowing sailing ships in the sky, but ended up processing it regardless through

the prism of his career thus far.

Nicholson‘s script presents young TV ad director Paul Groves (Fonda), glimpsed at the outset shooting

phony romanticism for his job whilst the wife he‘s divorcing (Susan Strasberg) comes to chastise him for

failing to show up to sign the papers whilst still evidently concerned and frustrated by his disconcerting

blend of charm and evasion. Paul, seeking release and self-understanding, has decided to enlist his

experienced pal John (Bruce Dern) as a guide and try LSD. John takes him to a pop-art-riddled manse on

the heights, seat of laidback but cautious maestro of narcotics Max (Hopper) and his court of blissed-out

freaks. Paul encounters the chic Glenn (Beach Party movie regular Salli Sachse) who flits about the edge

of the scene, and she‘s the first thing he sees as the acid starts to take effect.

Soon Paul is alternating between a supercharged version of the reality he shares with John – an orange he

holds becomes ―the sun in my hands, man!‖; the phrase ―living room‖ takes on strange new dimensions;

TV aerials on the hillside become a fresh Calvary for Paul‘s ailing soul – and hallucinatory visions,

churning together psychedelic patterns, dream-memories of making love to his wife, and fantasy

landscapes where he wanders alone in deserts and forests. Finally after hallucinating John as a bloodied

corpse, Paul flees into the city, and strays into another house where he befriends with a small girl but has

to run from the cops. Hopper won‘t take him in again for fear of bringing down heat, and he spends the rest

of the night roaming around the LA downtown in a paranoid delirium until he encounters Glenn again and

she whisks him away to her beachfront pad.

1967 proved a watershed year for Corman as The Trip scored a huge hit, albeit one only ever accepted

ironically by the counterculture. Corman, emboldened by its success, worked again on a big studio

movie, The St Valentine‟s Day Massacre, only to find himself discomforted by the experience and

commencing his march towards becoming a low-rent mogul instead. The Trip signals such a turn might

have already been in mind. Much as Paul‘s decision to try acid is based in his desire to understand himself

and push the psychic envelope rather than simply enjoy an illicit thrill, so the film serves in part as a

summary, Corman rummaging through his career, winnowing out key images and concepts. Paul wanders

fog-riddled, cobwebbed hallways as if he‘s slipped sideways, Buster Keaton Sherlock Jr (1924) style,

into one of Corman‘s Poe takes. The House of Usher makes a brief cameo appearance; other hallucination

scenes ricochet off the cheapjack medievalism of The Undead (1957) and the Bergmanesque fantasias

of The Masque of the Red Death (1964) by way of eaux-de-Tolkien and pseudo-De Quincey. Paul‘s

encounter with the sarcastic Flo (Barboura Morris) doing her laundry in a downtown Laundromat is a hard

lurch towards the wiseacre skid row character comedy that drove Little Shop of Horrors (1960).

The metafictional facet to Rock All Night (1956) and A Bucket of Blood (1959) returns as The Trip reckons

with Paul‘s status as a filmmaker doubting his own profession, and trying desperately to provoke his mind

into providing imagery charged with authentic emotional meaning. The return to the beaches and forests of

Big Sur, where Corman and Nicholson shot The Terror (1963), serves in part as self-satire for the director

and star whilst also assimilating that film‘s genre vocabulary into a more interiorised brand of fantasy and

a new way of mediating the concepts they filched from Poe, Lovecraft, and other classic fantasists, through

a prism of symbolic enrichment. The journeying motif of The Wild Angels is inverted along with the

perspective on outsider kicks, Fonda recast from rebel angel to sweater-wearing holy fool who can only

come into contact with authentic experiences of fear and destruction through substance abuse. Paul is

liberated into a dream world that‘s weird and terrifying, but which also contains wonders, as when he reels

down Sunset Strip, by day a tacky urban panoply, by night in the grip of acid a cosmos of light and colour.

Still, commercialism hides its little jokes – Paul watches one of his ads on TV before consuming his

tablets, with a frenetic Dixieland jingle heralding Psyche Soap, ―the only soap that makes you clean

inside…used by every star.‖

Meanwhile it‘s disconcerting to see Dern in such a solicitous mode as Paul‘s friend, trying to maintain the

safe limits of grounded readiness around Paul as he begins to freak out, tapping deep boles of guilt and

phthisic emotional reflexes along with kaleidoscopic sworls and pulsing energy streams. Corman company

regulars Dick Miller and Luana Anders flit by. Max‘s house has its own surreal reflexes, like a swimming

pool that extends under the living room. Paul sees himself as Christ on the mount, a mystic wanderer

escorted by a shamanka with a painted face and two hooded and cloaked riders. He encounters witches‘

brews and cotillions of pale-faced emissaries of death who strongly anticipate the post-apocalyptic mutants

of Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) and The Omega Man (1971); Corman‘s trippy visions

incidentally bridge last-gasp gothic horror and futuristic nightmares at the pivot of zeitgeists. Paul

imagines himself trussed up, masked and set alight in an arcane rite that suggests the discarding of Paul‘s

old self. Dreamscape and waking life blur into each-other as Paul sees his face and his wife‘s in the mirror,

both vibrating with colour.

Paul sees his wife with her new beau (Michael Blodgett), stirring bereft desperation, and imagines himself

under trial with a hepcat judge (Hopper again) who mounts him on a colourful electric chair, rides a merrygo-round, and assails him with images of political and artistic heroes and Paul‘s own, utterly empty ads.

Totemic accusations (―Bay of Pigs!‖) seem to indict Paul as a representative of a corrupt and violent

society. The judge diagnoses Paul with terminal self-involvement. As his state of consciousness shifts Paul

is flung out into the world, passing through a pastiche of Frankenstein (1931) as stitched-together

monstrosity is supplanted by the placidly brain-fried in befriending the innocent girl, whilst the excursion

to the Laundromat sees Paul pressganged into helping Flo with her washing but is rudely curtailed by

illusions of people trapped within tumble dryers. Dennis Jakob‘s terrific montage sequences drag Fonda

and viewer both through stroboscopic eruptions of colour-drenched, over-exposed footage, interspersed

with cabalistic logos and abstract designs. The two riding wraiths chase Fonda through forests and field

before at cornering him at the same stone gateway for the ocean where Nicholson lost Sandra Knight

in The Terror, and prove to be Paul‘s dualistic ladies fair in Bergman drag, demanding of Paul things he

can‘t always deliver.

Fonda ironically never seemed to be channelling his father‘s innate onscreen likability more than here in

playing a man whose fair and intelligent demeanour hide deep insecurities and blank spaces of identity: the

WASP as existential adventurer. Corman sometimes lets slip an acerbic perspective that doesn‘t entirely

buy what‘s apparently being sold. There‘s the spacey blonde Lulu (Katherine Walsh) who only talks in

superlatives (―Beautiful!‖) and flourishes of stoner poetry (―A big silver fish and a black-winged angel

met…and I went to sea for pearls.‖) to provide comic relief, and Max is awful quick to cut Paul loose

when his bothersome side-effects threaten his little kingdom, all on top of Paul‘s lysergic journey that

seems less hipster tourism than self-animated crisis. Paul‘s act of purgation and discovery is for a movie

man like himself essentially a hard and fast lunge through different imagistic zones culled from the trash of

his imagination – just as it is for Corman. The film was banned in some markets including the UK as an ad

for drug abuse, nonetheless.

But really The Trip proves less a paean to the proposed transformative appeal of the drug culture, than to

the act of using all that as a cover to creating surrealist and associative art momentarily freed from the need

to service a literal-minded, linear-shaped, commercially-driven pop culture or mere genre strategies. The

score, provided by Mike Bloomfield‘s newly-formed band The Electric Flag (billed as The American

Music Band), is certainly one of the film‘s most fun aspects, if also sometimes jarring in its leaps of style

and resulting effect. Corman‘s interest in earlier, more lawless times in American history and the drift

towards period portraiture in his last few works as director reveals itself in the semi-ironic use of Dixieland

jazz throughout, particularly over the lengthy final montage that brings Paul‘s trip to a climax, literally and

figuratively. A spirit of sprightly, Jazz Age gallantry infuses these fetid new-age procedures, charting a

subterranean link between the speakeasy and the stoner pad. The Charleston-ready ditties alternate with

throbbing organs and driving thrums in the fantasy sequences and regulation wailing guitar rock in a

nightclub scene as bodies gyrate and boobs bob amidst general ecstatics. Corman‘s trippiest effect comes

ironically before the pills are popped, his camera watching Fonda and Sachse move around a circular

balcony at a slightly skewed angle, space and perspective losing form, signalling the spree to come. Earlier

Corman keeps his camera fixed and pivoting the survey the tribal circle whilst a joint is passed for the

postmodern powwow; Hopper would pinch the shot for Easy Rider (1969), and so would That „70s Show.

The film‘s main flaws reflect Corman trying to pad out the running time when inspiration wanes and the

need to inject some sex – both a sequence of Paul in bed with his wife, bathed in swirling colours, and

sitting in a tavern listening to a rock band whilst the freaks party down, go on much too long. The very end

was altered initially to appease the forces of squaredom with the threat of crack-up caused by the trip,

literally illustrated by fissures appearing across a freeze-frame of Paul gazing thoughtfully out upon a

bright and endless ocean. The effect has been discarded in some versions. But still the ambivalence of the

ending makes plain that sort of thing wasn‘t necessary, as Glenn warns the now all-loving Paul, ―It‘s easy

now - wait ‗til tomorrow,‖ to Paul‘s stoic reply, ―Yeah, well, I‘ll think about that tomorrow.‖ The going up

is a new book of revelation, but so is the coming down. It‘s all an absurd strew, of course, but also an

impossibly rich one, a testimony to the pleasure of seeing Corman entirely abandoned to his medium for

the only time in his career, and a pure exploration of what Yeats called the place where all poetry starts,

the ―foul rag and bone shop of the heart.‖ Hopper‘s Easy Rider and The Last Movie (1971) were two

obvious children that would shake and then reassure the Hollywood bigwigs; Stephanie Rothman would

take up aspects under Corman‘s New World banner on The Velvet Vampire (1971). But The Trip‘s

influence runs right through the American New Wave and its inheritors, from Antonioni‘s Zabriskie

Point (1970), Altman‘s The Long Goodbye (1973), Coppola‘s Apocalypse Now (1979), to Stone‘s The

Doors (1991), Nolan‘s Memento (1999) and Inception (2010), Kubrick‘s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), and

Lynch‘s Mulholland Drive (2001), all revealing kinship claimed and licence taken.

Zorba the Greek (1964)

film freedonia, 28 january

Director/Screenwriter: Michael Cacoyannis

My father Douglas Heath died late in 2018 at the age of 71. Dad was a lifelong cinephile. Many of the

films he held in fierce affection were movies he saw during his late teens and twenties, a time when he was

often homeless and constantly adrift in life, but also intellectually voracious and consuming culture in any

way he could. He told me he knew my mother was the woman for him when he took her to see Peter

Brook‘s Marat/Sade (1967) at a revival screening and she loved it (a previous girlfriend had walked out

during the opening credits). Later in life when asked what his favourite movie was, he tended to name one

of two films as his favourite. One was the Robert Wise-directed, Val Lewton-produced The Body

Snatcher (1945), which he held in particular esteem in part because of its dreamlike evocation of the

Scotland he‘d been forced to leave as a child when his father decided to emigrate. But the movie he most

consistently named was Michael Cacoyannis‘ Zorba the Greek. It‘s not hard for me to see why Dad was so

particularly passionate about Cacoyannis‘ film. Like Zorba, my father had done every job known to

humanity, could make friends in an empty room, had talents he wouldn‘t sell, and those he did usually left

him rolling amidst the wreckage wondering what went wrong. I remember the first time I watched the film

with him, as a kid, and being confused at the switchbacks of high tragedy and knockabout comedy

throughout. I asked him what kind of movie this was. Dad responded, ―It‘s life.‖

Cacoyannis‘s oeuvre in general and Zorba the Greek in particular perhaps need revival these days.

Alongside American blow-in Jules Dassin, Cacoyannis captured the world‘s attention for Greek film, well

before the arrival of Theo Angelopoulos and the current brace of figures like Yorgos Lanthimos and

Rachel Athina Tsangari. If Zorba the Greek still has any cultural cachet it‘s certainly thanks to its famous

theme by composer Mikis Theodorakis, which became emblematic for the post-WWII Greek diaspora and

introduced something of the spirit of Greek rembetiko music to the world at large. Ironically the theme‘s

popularity might have done the movie few favours, perhaps making it seem like escapist exotica from

another age along with the likes of Black Orpheus (1959). Cacoyannis‘ reputation meanwhile never quite

recovered from the bruising reception to his follow-up to Zorba the Greek‘s great success, The Day The

Fish Came Out (1967), a film which, in spite of its gutsiness in trying to be a queer-themed comedy at a

time when that was still pretty outre, still can‘t even claim cult status. But Cacoyannis‘ career also included

great, highly underappreciated adaptations of Euripides, including Elektra (1962) and The Trojan

Women (1971), and he reunited with Zorba the Greek star Alan Bates in the early 2000s for a version of

Chekhov‘s The Cherry Orchard.

The film was an adaptation of the novel The Life and Times of Alexis Zorba by Nikos Kazantzakis,

(called Zorba the Greek in English-language editions), who had earned international interest for

contemporary Greek writing up until his death in 1957. Kazantzakis‘ art was built around apparently

contradictory precepts, contradictions that gave his books their feverish sway. As a Marxist writer

Kazantzakis wanted to dig into the authentic character of Greece‘s working and peasant classes, and he

initially annoyed cultural watchdogs by writing in demotic or popular modern Greek. But Kazantzakis was

also compelled by a defiantly personal religious sensibility, which gave birth to his other best-known

book, The Last Temptation of Christ, filmed by Martin Scorsese in 1988: the infamy that met Scorsese‘s

film had already been anticipated by the reaction of religious authority to the novel. Zorba the Greek was

Kazantzakis‘ attempt to summarise the vitality of the national character, so long buffeted by poverty and

oppression since the ancient glory days, presented through the title character who‘s uneducated but

possesses great wisdom after a long, hard-knock life, and sufficient unto himself. Somewhat ironically, the

character was bound to become synonymous with the Mexican-Irish actor cast in the film role, Anthony

Quinn.

Quinn was another man who identified deeply with the character nonetheless, as an actor who‘d lifted

himself out of a childhood of grinding poverty through creative talent and achieved a career as one of

Hollywood‘s perennial supporting players, in large part thanks to his ready capacity to play any ethnicity

under the sun. Quinn owed some of his early career traction to marriage to Cecil B. DeMille‘s adopted

daughter Katherine, and the filmmaking titan gave Quinn a lot of work, eventually producing Quinn‘s lone

directorial outing, a remake of his father-in-law‘s The Buccaneer (1958). Quinn eventually captured two

Oscars in the mid-1950s for Viva Zapata! (1952) and Lust For Life (1956), playing the more degraded

brother of the folk hero in the former and Paul Gauguin opposite Kirk Douglas‘ Vincent Van Gogh in the

latter. But it wasn‘t until Federico Fellini cast him in La Strada (1954) that Quinn gained traction as a

leading man and became a popular figure in European as well as Hollywood film. Often cast as a Latin

roué in the ‗30s and ‗40s, the grizzled and thickening Quinn became exalted for his ability to play strong,

earthy, eruptive personalities, usually with a brutish streak, who thrive at the expense of the more neurotic,

delicate, or victimised people they orbit. By playing Zorba, Quinn tried to revise his screen persona in

inhabiting a similar role who nonetheless tries to pass on some of talent for life to others.

Cacoyannis laid specific claim to the material with his emphases. Cacoyannis came from Cyprus and his

father had been closely involved the British administration of the island at the time. Cacoyannis spent

much of his youth in Britain, including a stint in the RAF during World War II, and so the novel‘s narrator

and viewpoint character Basil became a half-Greek, half-English intellectual trying to get back in touch

with his roots. A subplot involving his ill-fated romance with a local widow was emphasised and

refashioned into a tale within the tale close in nature to one of the classical Greek tragedies sporting a

female figure of titanic suffering Cacoyannis was so compelled by. Basil, played by Bates, is on the way to

Crete, having inherited a small property there that belonged to his father incorporating a seaside shack and

a disused lignite mine. When the ferry to Crete is delayed by a storm, Basil waits with other passengers in

the terminal; Cacoyannis offers the subtly weird touch of the sound of the storm abating as Basil senses a

strange presence, and notices Zorba staring through the fogged glass. Zorba, on the lookout for an

opportunity, quickly attaches himself to Basil, offering to serve him in any capacity he requires. Zorba

seems initially a sort of vulgar, unctuous grotesque borne out of the storm, but Basil quickly takes a shine

to his energy and gains increasing respect for him as he reveals surprising turns of personality, like his

refusal to offer his talent for playing the santuri: ―In work I am your man, but in things, like playing and

singing, I am my own – I mean free.‖ Basil employs Zorba specifically to get the mine working again, and

they board the ferry together.

The corner of Crete where Basil‘s land is proves poverty-stricken and defined by a finite balance the two

arrivals find themselves doomed to disturb. The two men spend their first night in the town in a crumbling

guest house amusingly styled the Hotel Ritz, owned by Madame Hortense (Lila Kedrova), an aging former

dancer from Parisian nightclubs and courtesan who airily regales them with accounts of her once-wild life.

She dances saucily with both men, although it‘s Zorba who ends up in bed with her, after Basil, with the

heedlessness of youth, humiliates her when he can‘t help but laugh at her increasingly overripe anecdotes.

After setting up home in the shack on Basil‘s property, he and Zorba hire some workers and tackle the

mine, but find the wooden props are too badly rotten to risk starting operations, after Zorba is almost

buried alive twice. Spying a large forest down the coast, Zorba travels there and finds it‘s owned by a

monastery; after befriending the monks, he hits upon a plan to use their lumber to rebuild the mine,

requiring a large zipline to be built down the side of a mountain. Basil sinks the last of his capital into

supporting Zorba‘s plan, whilst Zorba, who considers passion a veritably holy thing, in turn encourages

Basil to romance a young and well-to-do widow (Irene Papas) who‘s the object of desire for every man in

the village, but only the young stranger has a chance with her after he aids her gallantly.

Zorba the Greek revolves around fundamental oppositions, represented most immediately by Basil and

Zorba, the difference between head and heart, reason and instinct, proletarian and intellectual, modernity

and archaic lifestyles. Basil‘s cautious and thoughtful manner stands in near-perfect opposition to Zorba‘s

gregarious, life-greedy sensibility, but the two men become inseparable precisely because they‘re such

natural foils, and has something to offer the other. Basil‘s stiff Anglo-Saxon half wants to steer clear of

intense and potentially unstable situations, whilst Zorba believes that‘s the only way to go: ―Living means

to take off your belt and look for trouble.‖ The essence of Kazantzakis‘ book, a dialogue of values and

viewpoints between two long alienated ways of approaching the world represented by two mismatched yet

amicable avatars, comes through. Zorba has plenty of literary antecedents, of course, as the voice of

common wisdom, stretching back to Hamlet‘s graveyard digger. Zorba the Greek never proposes that

Zorba is a saintly character, although he also has aspects of a holy fool: he‘s often absurd, given to

expansive inspirations and notions that don‘t ever quite seem thought through, and unable to curb his

appetites. The main lesson he teaches Basil is that tragic moments in life can‘t be avoided, and it makes

more sense to celebrate living as something sufficient in itself than to live in fear of consequence or search

for absurd designs behind it all.

Zorba‘s own melancholy history is grasped at intervals, as he memorably answers Basil question whether

he ever had a family with the admission, ―Wife – children – the full catastrophe.‖ Later, after one of his

frenetic moments of incantatory dancing, he confesses to Basil that he danced the same way after his

young son died. In a drolly comedic sequence, he becomes something like a literal Pan figure, as he goes

to take a look at the monastery‘s forest and scares the hell out of some of the monks when they find him

hiding, so filthy from his forays in the mine they think he‘s a literal devil rather than his mere advocate.

Zorba plays this to his advantage as all the monks come out to hunt the demon only to finish up getting

drunk with him. Zorba pronounces, with dubious theology if certain feeling, that the only sin God won‘t

forgive is if ―a woman calls a man to her bed and he does not come.‖ Zorba gets along like a house on fire

with the lusty, romantic Hortense, who subsists in a bubble of melancholic recollection of her glory days as

exalted concubine for warriors and statesmen, an embodiment of forgotten belle époque and spirit of

sensual exaltation who remembers being bathed in champagne by her harem of naval officers who then

proceeded to drink the liquor off her body. But Zorba has no intention of marrying again or settling down,

taking up with a young tart when he goes to Chania to buy tools and parts for his project. Basil semiaccidentally commits Zorba to marrying Hortense when she insists on hearing the contents of a letter he

writes his friend, substituting romantic feelings for Hortense for Zorba‘s actual boasts of erotic

adventuring.

When Kazantzakis wrote his novel he was trying to bridge the ways Greeks had of looking at themselves,

and to forge a new literary zone for himself and followers to inhabit. When Cacoyannis made his film, he

faced the task of making a relatively esoteric piece of regional portraiture interesting to international

viewers. Cacoyannis had been directing films since 1953‘s Windfall in Athens, but with Zorba the

Greek caught a similar wind to what had made Fellini‘s La Dolce Vita (1960) and Dassin‘s Never on

Sunday (1960) big worldwide hits. Cacoyannis absorbed the new lexicon of New Wave cinema, as Zorba

the Greek is replete with jump cuts, zoom shots, and interludes of hand-held shooting, and took to the latter

technique in particular as a way of getting close to his characters and evoking their extreme emotions.

Over and above that, Cacoyannis might as as well have been trying to reconcile principles of early ‗60s art

cinema style with more traditional theatrical understandings of performance and character. Moreover,

Zorba‘s unpretentious and expansive sensibility repudiated the navel-gazing tenor of the Italian

―alienation‖ mode and the hyperintellectualised aspects of the New Wave, and anticipated the oncoming

age of the counterculture, when Kazantzakis‘ writing would find many new fans.

Download Roderick Heath 2019 Film Writing

Roderick Heath 2019 Film Writing.pdf (PDF, 1.32 MB)

Download PDF

Share this file on social networks

Link to this page

Permanent link

Use the permanent link to the download page to share your document on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or directly with a contact by e-Mail, Messenger, Whatsapp, Line..

Short link

Use the short link to share your document on Twitter or by text message (SMS)

HTML Code

Copy the following HTML code to share your document on a Website or Blog

QR Code to this page

This file has been shared publicly by a user of PDF Archive.

Document ID: 0001935517.