YoungFreudiansFall (1) (PDF)

File information

Title: Microsoft Word - Yf3.docx

This PDF 1.3 document has been generated by Word / Mac OS X 10.10.5 Quartz PDFContext, and has been sent on pdf-archive.com on 16/03/2018 at 18:56, from IP address 64.136.x.x.

The current document download page has been viewed 344 times.

File size: 17.37 MB (33 pages).

Privacy: public file

File preview

1

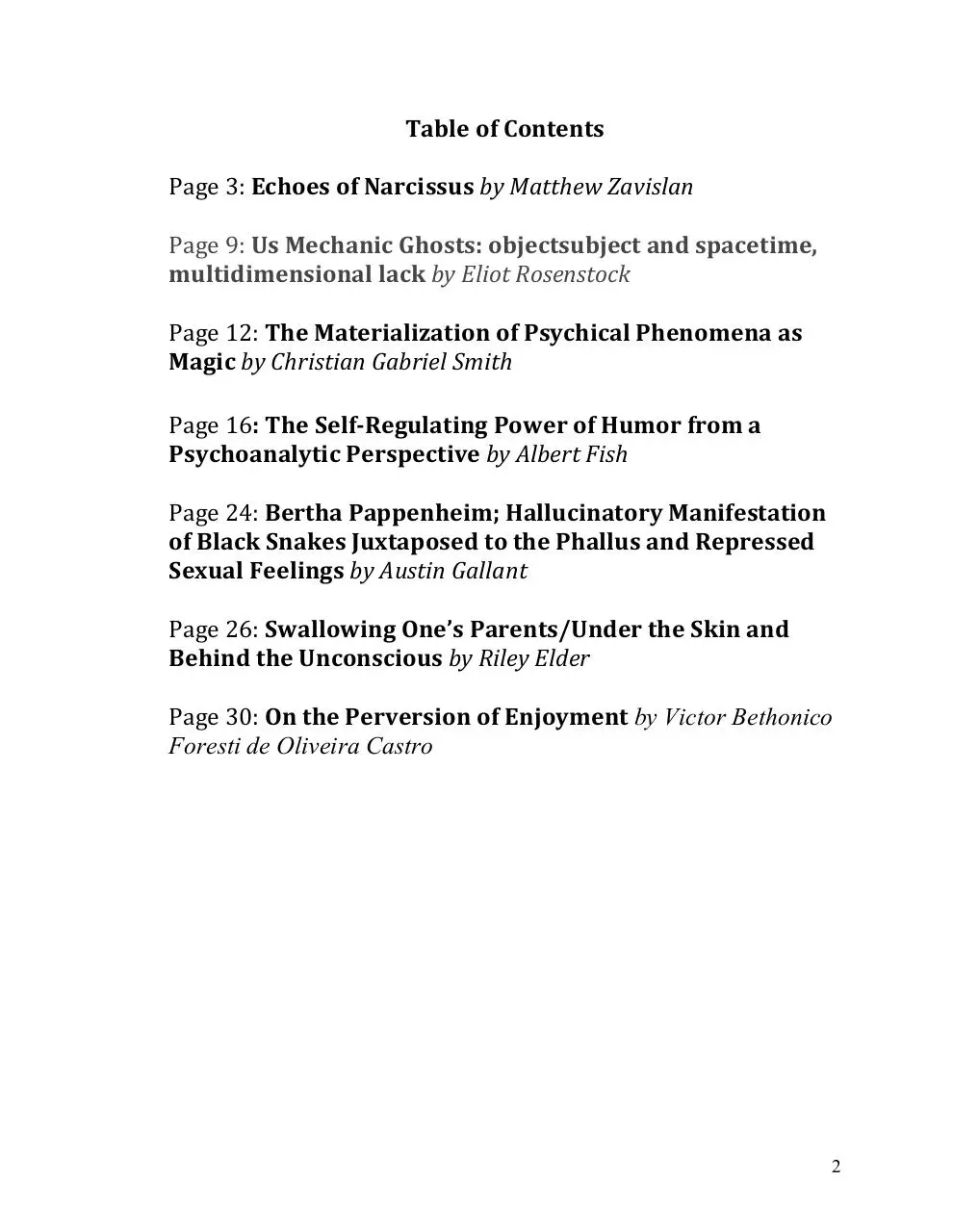

Table of Contents

Page 3: Echoes of Narcissus by Matthew Zavislan

Page 9: Us Mechanic Ghosts: objectsubject and spacetime,

multidimensional lack by Eliot Rosenstock

Page 12: The Materialization of Psychical Phenomena as

Magic by Christian Gabriel Smith

Page 16: The Self-‐‑Regulating Power of Humor from a

Psychoanalytic Perspective by Albert Fish

Page 24: Bertha Pappenheim; Hallucinatory Manifestation

of Black Snakes Juxtaposed to the Phallus and Repressed

Sexual Feelings by Austin Gallant

Page 26: Swallowing One’s Parents/Under the Skin and

Behind the Unconscious by Riley Elder

Page 30: On the Perversion of Enjoyment by Victor Bethonico

Foresti de Oliveira Castro

2

Echoes of Narcissus

By Matthew Zavislan

(René-Antoine Houasse, Narcissus,1688-1689)

The name given to this fragmented body of texts—Young Freudians— is a name in

which a curious directive is heard: Go back to Freud; but also, make him young again. Go

back, read his texts, but don’t just read them as artifacts of a dead history. The theoretical

demand made of this journal is not the reconstruction of a historical Freud, but the creation

of new forms out of the discursive possibilities his texts opened up. One must thus

understand the creative potential of such an endeavor as essentially metamorphic: a

transformation of Freud that goes beyond the Freudian corpus by taking up the very

discourse it instantiates. The task of the theoretician can no longer be concerned with a

radically original creation ex nihilo—as perhaps Freud was—but with the taking up of

another’s voice in order to situate new meanings in the hollows left by the reverberation of

these discourses on the surfaces of different individuals and histories. The return to Freud

demanded by this journal is thus not simply a matter of going back to a past in which

everything was already-‐‑said, but in finding within this already-‐‑said the echoes of one’s own

saying. If post-‐‑modernism has reduced everything to pastiche, it is only in the inspired and

transformative repetitions of an already existent discourse that we may bring youthfulness

to the psychoanalytic discourse Freud made possible.

But I wish to begin by returning to another youth, so very close to Freud, although

born so much before him. The story is one relayed to us by Ovid1: In Boeotia, a beautiful

boy was born to the nymph Liriope following her rape by the river-‐‑god Cephisus. When this

1

I am taking the liberty of not citing each and every line by Ovid, as all quotations occur from the same 2 pages on Book 3 of the

Metamorphoses. Quotations, unless otherwise attributed, should be presumed to be Ovidian.

3

anxious mother asked the seer Tiresias if her child would live a long and happy life, the seer

replied that it would be so only “if he never knows himself.” This child was called Narcissus.

As Narcissus reached maturity, his beauty attracted the attention of many young men and

women. And yet, Ovid tells us, “in [Narcissus’] slender form was pride so cold that no youth,

no maiden touched his heart.” Eventually, one of these scorned suitors turned their hands

to heaven and prayed to the goddess Nemesis that Narcissus—cold as he was towards the

love offered to him—be in turn cursed to love only himself and yet be forever frustrated in

the consummation of that love. Nemesis heard this prayer and so, one day, as Narcissus

was bending down to drink from a clear spring he caught a glimpse of his reflection borne

in its waters.

The tragedy of this tale is well known: Narcissus finds himself besotted with the

image of the beautiful boy he sees staring back at him. He admires himself, taking note of

his own beauty and whispering words of love to the boy staring back up at him. At first he

rejoices, because he sees the boy in the pool repeat his words of love, and rise to meet the

kisses Narcissus would plant upon him. Yet each time Narcissus reaches out towards his

image it eludes him. Foregoing all sustenance, Narcissus wastes away staring vainly and

hopelessly at his beloved image reflected up at him from the crystalline waters of the pool.

Finally realizing that he loves his own image, Narcissus finds morbid comfort in that fact

that he and his beloved reflection “shall die together in one breath.”

Even on this basis of this roughest of outlines it should be easy for even the least

familiar reader to see how the Narcissus myth became a fertile ground for the

extrapolation of psychoanalytic concepts. Not only does the myth dramatize the

identification of the child with his own specular image, eventuating the formation of an

image-‐‑ideal of the self that would become the locus for the management of sensory and

affective perceptions—the ego—but the resigned suicide of Narcissus who would rather

die than separate from his beloved reflection reveals and foretells the “death instinct”

which operates at the heart of this living body of erotically charged identifications. It

should thus come as no surprise that Narcissus is a common—indeed, a near ubiquitous—

mythological fixture of psychoanalytic writing.

Indeed, Freud employed the metaphor of a “primary narcissism” to describe the

tendency— notably found in infants, magic users, and neurotics—to overestimate the

reach and potency of one’s desires to the extent that they become indistinguishable from

the world they inhabit. At a formal level, this narcissistic tendency allowed man to cope

with his environment by solidifying an image of his place in it. Thus, even at the moment of

catastrophe man’s place is reaffirmed: this catastrophe was meant for him, was a reflection

of his own wrongdoing. As a real object, the world is mute. It speaks only when imbued and

invested with/by our desires. . Narcissus sees his image as an object, but it is the non-‐‑object

par excellence—in Ovid’s words: “a bodiless dream”. Yet, in order that this mirrored

relation between self and world to be maintained, one must set up resistances against

those forces which would disturb the tranquility of this reflection. This site of resistance is

the ego. Thus, in the narcissistic mode, the fantasy object displaces the real object in order

to uphold the unity of the ego and its world

Following this extrapolation, Jacques Lacan posited that during the mirror stage of

development in which a child first recognizes his own image in the mirror, the libidinal

force of the identification with this image is that “in comparison with the still very

profound lack of coordination in his own motor function, that gestalt is an ideal unity

4

(Lacan, 113).” Here the mirror stage appears as an ideal unity compensating for the lack of

control the child has over its body. However, this function of the ego-‐‑image is not limited to

the child, and it does not take any amount of effort to see here the precursor for the lack of

control over one’s body when afflicted with the pains of aging and the inevitability of loss

(or the whole host of other ways in which the body is fragmented by its encounter with the

world). While our motor coordination improves, our control over our bodily and affective

mechanisms is never total, exposed as they are to the outside of oneself.

“In analytic experience,” Lacan concludes, the ego represents the center of all

resistances to the treatment of symptoms,” because we, like Narcissus, invest so much of

ourselves into the constancy or clarity of the image we have of ourselves (Lacan, 118). Now

let us recall that in Ovid’s tale, it is the tears of Narcissus that disturb the reflecting pool.

When he cries, unable to attain that which he desires, “his tears ruffled the water, and

dimly the image came back from the troubled pool. In order to maintain sight of his beloved

image, Narcissus thus must to dam himself up, lest his emotion overcome the beloved other

to which he responds. Thus we can see the faculty of repression at work: when the

situation in which one finds themselves runs contrary to the ego-‐‑identifications Narcissus

has made for himself, the clarity of the ego is obscured. Were the other of reflection—the

narcissistic ego—a real other of flesh and blood, then Narcissus’ tears would not so easily

efface them. And yet, so simple and straightforward a claim itself risks obscuring the

reflection we have here started for Narcissus, himself of flesh and blood, certainly seeks to

efface himself.

Ovid proclaims that the tale of Narcissus introduced a new insanity: one in which

only the displacement or repression of feeling would enable the pursuit of the object that

elicited such a feeling. In order for Narcissus to gaze into the eyes of his beloved he had to

hold back his tears—of joy or sorrow—that mark the emotion which impels him towards

himself. Under his own spell, the consummation of love Narcissus longs for forever denied

to him by himself who sought it, in the very gesture by which the beloved was designated

as an object of love. Yet it is precisely this ambivalence with regard to his image that binds

Narcissus to himself. His moment of identification with his image is also a moment of

alienation. Certainly Narcissus professes his singular love for this image of himself, but the

very richness of this love is his poverty. “While he thus grieves [… Narcissus] beats his bare

breast with pallid hands” until his white skin turns red and bruised. He resents himself for

letting his image fade. Or perhaps he resents his image for fading, or the spring for not

remaining still despite his tears.

Love thus oscillates with hatred. Without the mirror to provide him with the

persistence of his image, Narcissus’ aggression is vented elsewhere. The moment of

identification is simultaneous with a moment of accusation. He resents the distance of his

beloved, resents him for not being able to embrace him. But also resents him for his

closeness: “I would that what I love were absent from me,” so that he could consummate

his love for himself without also effacing himself. If only “I might be parted from my body!”

If only… then Narcissus wouldn’t need cry, and his tears would not disturb the reflecting

pool.

Narcissus might wish that “he that is loved might live longer” than himself, but

knowing that he will die along with his image Narcissus wills their mutual death. Thus the

strange simultaneity of suicide and sacrifice that Lacan finds in narcissism, or that Freud

identifies with a death instinct operating at the core of erotic attraction: a devastation one

5

cannot bear but cannot bear being without; a desire for a face to see itself immobilized in a

persona—a death mask. Narcissus’ recognition of himself is thus simultaneously also a

misrecognition; not just because, as Lacan puts it, “man’s ego is never reducible to his lived

experience,” but more fundamentally because the face in the mirror is simply the of a unity

that never existed as such.

The self-‐‑image is not a singular identification made on account of some fundamental

truth concerning oneself, but is rather a series of objectifications of moments and others,

like photographs snatched from the void. Like a photograph—which is not the simple

capture of a frozen moment, but the creation of a new context taken out of context— these

objectifications of himself don’t spring spontaneously from the desire of the youth, as if he

were the agent of creation in his own ego. Rather, as he looks in the mirror Narcissus

“admires himself for what he himself is admired.” He immediately looks at himself a certain

way: admiring his skin, his jaw and his hair. He is already looking at himself as if through

another. His autoeroticism is mediated, and hence no longer truly autoerotic: it requires an

other.

Yet this might seem puzzling, as I have up to this point insinuated that Narcissistic

reflection takes place in the absence of an other, there were a deluded boy falls in love with

a phantasm of himself. Certainly there are others, but Narcissus scorns them. Certainly they

do not mediate his desire. So where in our tale does this other appear? Narcissus “admires

himself for what he himself is admires” and not only is there thus the presence of the other

and his desires, but also a strange doubling of Narcissus himself. He sees himself in the pool

and, in seeing himself, sees the other see him. He admires himself, and so also sees that this

object of desire desires him also. Narcissus cannot see himself as immediately desirable,

but rather only on the condition of being seen as such by this reflective other which he has

created for himself. (Is this experience so foreign to us? Are we too not the creators of

phantasms in the reflective surface of our minds, which can assure or attack us; validate or

gnaw away at self-‐‑reflection we have hoped to freeze for ourselves.)

However, as should be clear this reflective phantasm is not the other. Even

Narcissus feels the gravity of this truth: “Oh I am he! I have felt it…” Is the mediation thus

wholly imaginary? Certainly not. Rather the other has escaped reflection precisely because

it/they are the surface upon which reflection is cast. I speak here of the waters of the spring

upon which Narcissus sees his reflection. Julia Kristeva quips: as “a symbol of the maternal

body, is it not after a fashion penetrated by the youth who thrusts his image into it?”

(Kristeva, 113) For Freud, “a human being has originally two sexual objects: himself and

the woman who nurses him…” One can find in narcissism the simultaneous merging and

displacement of these objects. The wholeness promised by the maternal figure mediates

the original autoeroticism of the infant such that she becomes the surface onto which and

against which the narcissistic image is cast. If one cannot achieve self-‐‑satisfaction, it is the

fault of the woman who has denied it to him, or who at least has failed to ready him to take

it for himself. When Narcissus cries, he curses the watery reflection for leaving him, even

though it is his own tears that break it.

One might say that the spring is the sexual object proper to Narcissus. The spring is

commanded to hold herself still, keep her waters clear and virginal, so that man might see

himself reflected therein. It cannot be overcome by flows of its own hysterical emotion, else

it’s reflective capacity be ruined. The pool is the other whom we demand give us back a

reflection of our self as we see it; that is, an ego. Thus, as Kristeva remarks, this possession

6

of the image “holds only nothingness for store for the other, particularly the other sex

(Kristeva, 113).” The maternal spring—woman—is “simply a medium” for the projections

of Narcissus. Yet, because the beloved other that Narcissus seeks is not simply his own

image, but himself as the other, the spring can provide him only a phantasm of this object of

desire.

The tragic aspect of the myth is not that his beloved escaped him, but that his

beloved was fated to escape him. Thus, “if the Narcissus adventure is perceived as insane

by Ovid […] insanity comes from the absence of an object, which is, in the final analysis, the

sexual object” (Kristeva, 116). This lacking object “gives sexual existence to anguish” and

thus Narcissus becomes the subject of reflection and death, capable of reflecting on himself

and on death. Thus reflecting, Narcissus finds himself as desiring both himself and his

death in the same movement of longing. In the end, the autoeroticism of Narcissus finds its

only joy in the clarity with which he perceives his own ruination. Narcissus: the avowed

atheist, Sisyphean man: pushing boulders up a hill for the pleasure of seeing his own

destitution.

As a manner of conclusion, permit me to bring back into this tale an aspect we have

forgotten. One that, for all the treatment given to this myth by philosophers and

psychoanalysts, has been relegated to a place of silence even as she appears woven most

apparently through Ovid’s tale. Recall that Narcissus had many nameless, anonymous

suitors. But of these, Ovid singles out one who is particularly besotted with the beautiful

boy: accursed Echo. Having hidden the details of her father’s infidelities from Juno, his

wife, by the cleverness of her speech, Echo is cursed by the jealous goddess to forevermore

only be able to repeat the words given to her by others. Catching a glimpse of Narcissus,

Echo is stricken by love for him but, owing to her predicament, is unable to call out to him.

Instead, Ovid tells us that Echo follows the boy at a distance, waiting for an opportunity

where she might speak to him. Then one day, Narcissus is separated from his companions

and calls out: “Is anyone here?” Echo cries back, “Here!” Narcissus hearing in answer “his

own words again” is unsure of her presence, and so Echo rushes forth from her hiding place

among the trees seeking to embrace him. Yet Narcissus flees from her as he has from so

many others, saying to her: “Embrace me not! May I die before I give you power over me!”

Yet Echo, overcome by her love for the beautiful youth repeats only some of his words: “I

give you power over me!”

It might thus be said that in the tale of Narcissus there are two mirrors: the maternal

spring, bearing one’s image in her waters; and, the more profound, creative mirror of Echo.

Echo doesn’t give back the ego, but gives herself to him in response. In this mirror is not the

still emptiness of the Narcissus’ image, but borrowed words weaving subjectivity.

Narcissus ignores Echo, hearing only a stilted reflection of himself; a lesser, unstable, more

hysterical copy. He does not see the creativity of the nymph who gives him back to himself

in love, who gives herself to him as an inspired reflection. Even forced into this role by the

unabashed lechery of her father, Echo manages to speak herself: she reaches out to

Narcissus but her mirror is not clear enough for him. There is some of her in it. Her life, her

words, and her love obscure his own reflection. He sees that it would be contaminated by

this entwining of her into him and he is afraid. Still greater is his fear that this entwining

becomes an intertwining so that his own reflection would contain her face: her eyes gazing

back into his own. This quiet pang of responsibility disquiets him—what if I can no longer

see myself? Not because I have vanished, but because I have become a chimera, capable

7

only of gazing at myself with your eyes? I see a stranger in the mirror that looks like you,

and I only have recognized myself. I might like what I see, but the mirror is no longer clear.

The mirror of Echo is blasphemous.

Perhaps one can imagine that Narcissus is looking for the very love that Echo and so

many others offer to him, but this love doesn’t reflect himself and so he rejects her. This

situation is not hard to imagine: a person has a generally misanthropic attitude and scorns

the love they are offered by others because they are certain that their friends will all turn

out to be false friends, or otherwise won’t live up to their expectations. The apparent

certainty of this thought then prevents them from forming close bonds with others, thereby

confirming the validity of the same misanthropic outlook that instantiates the paranoia. It

is unsurprising, therefore, that Lacan thus attributes to Narcissus a kind of paranoiac

thinking, always on the lookout for what would disturb the ideality of the self to which it

clings. It is, says Lacan, “the very delusion of the misanthropic, beautiful soul, casting out

onto the world the disorder that constitutes his being (Lacan, 93).”

References

Kristeva, Julia. “Narcissus: The New Insanity” in Tales of Love, trans. Leon Roudiez.

Columbia University Press; April 15, 1987

Lacan, Jacques. “Aggressiveness in Psychoanalysis” and “The Mirror Stage” in Ecrits, trans.

Bruce Fink. W. W. Norton & Company; January 17, 2007

Ovid Metamorphoses, trans. Frank Justus Miller. Barnes and Noble Classics, 2005.

8

Us Mechanic Ghosts:

objectsubject and spacetime, multidimensional lack

by Eliot Rosenstock

(Edited image from “Bladerunner 2049,” the replicants existing simultaneously in their

individual objectsubject planes as well as spacetime.)

Without the proper framework for existence, our ignorance trips us up, ignorance

creating a positive feedback loop unto itself, expanding itself, overshadowing everything.

This is the nature of all frameworks, but a more accurate framework looping upon itself has

a different nature than one based off of an inaccurate understanding of the nature of being.

The accurate framework seems to allow the subject to move fluidly through existence. Why

bother with more metaphysical frameworks when Kant has long been buried in the

ground? A being-‐‑savoir (an expertise of being) can only be built through an accurate

framework of reality and the nature of inhabiting reality, and the being-‐‑savoir is highly

recommended by this author for all those who have the pleasure of existing.

The objectsubject field is a metaphysical framework for organizing the existence of

an organic being simultaneously as the center of one metaphysical universe (the

objectsubject field of a particular subject) along side the organic being’s inhabitance in

spacetime, which is the shared space of existence, i.e., the physical realm.

“What do you think you are, the center of the universe?” the Big Other cries to us.

Within our phenomenological investigations we are in fact, the immovable center of

the universe from which all context drives. We have a left and right, a front and back, which

9

Download YoungFreudiansFall (1)

YoungFreudiansFall (1).pdf (PDF, 17.37 MB)

Download PDF

Share this file on social networks

Link to this page

Permanent link

Use the permanent link to the download page to share your document on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or directly with a contact by e-Mail, Messenger, Whatsapp, Line..

Short link

Use the short link to share your document on Twitter or by text message (SMS)

HTML Code

Copy the following HTML code to share your document on a Website or Blog

QR Code to this page

This file has been shared publicly by a user of PDF Archive.

Document ID: 0000745933.